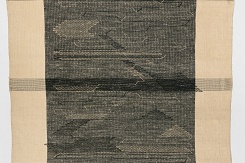

Color was essential to Bergner’s work, not simply because they provide different ways to articulate a medium, but also because they strengthen the work in a plastic sense. If painting had been spurned by Constructivists and the Bauhaus as an art form that did not speak of reality and lacked social commitment, color—as an aspect of light—continued to be considered approvingly by both vanguards. In terms of perception, aesthetic enjoyment is not only formed by the weave, there is also something innate in color that triggers sensations.17 For Bergner, as one of the oldest fields of human activity, textile demonstrated the fundamental law of all plastic creation.18

After a six-month stay at the University College of Dyeing in Sorau,19 where she studied dyeing processes, on 6 October 1930 Bergner received her diploma from the Bauhaus, which she complimented with a professional examination as a weaver in the city of Glauchau in Saxony.20 She later became the manager of a manual textile factory in Königsberg, East Prussia, where she had previously lived for a time.

In 1937 she married Hannes Meyer, having become close to him during her trip to the Soviet Union. During her time there she developed fabrics for furniture factories, primarily in Moscow. In 1935, the first station in the Moscow metro was opened. Bergner had participated in the work along with the so-called Bauhaus Brigade, who arrived in the Soviet Union some time in 1931. The Brigade, led by Hannes Meyer, consisted of eight colleagues and students. The team focused on urban planning for cities, including Moscow,21 conceived of as a construction discipline and following the tenets of social realist architecture. Bergner developed her work between 1931 and 1936 in the Decorativtkan textile factory, which had some 650 workers and an annual production of 3.5 million meters of fabric intended for furniture, curtains and the like. Here she created more than forty drawings22 contributing to the needs of the Soviet government’s various five-year plans.23

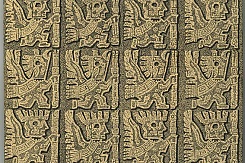

When Lena Bergner first arrived in Moscow, it was in the middle of the government’s first Five-Year Plan (1928–1932). Artistic and cultural production was focused on abstraction, constructivist theory and propaganda work, to which Bergner responded with pictorial designs and themes based on the socialist city, the radio and the new metro system. However, for the second Five-Year Plan (1933–1937) there was a clear shift in her designs from geometric abstraction to folkloric themes, since the government’s plans in this period focused on propaganda exalting the socialist lifestyle, a theme demanding decorative elements incorporating oral and folkloric motifs.24 Bergner enthusiastically assumed an ideological commitment to the USSR and it was here that she made what are largely considered her most important and innovative fabrics.

_crop.jpg?w=245&h=163&c=1)

Kopie.jpg?w=245&h=163&c=1)