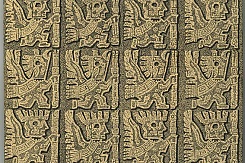

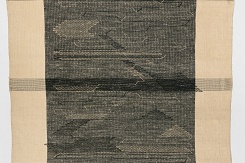

During the Dessau Bauhaus period (1925–1932) members of the Weaving Workshop, particularly Albers, explored complex color and shape patterning in conjunction with complex weaving structures such as multi-layered weaves. There was an increased emphasis on machine-like precision and experimentation with synthetic fibers. These emphases were partly due to the growing technical proficiency of the members of the workshops, as well as to their analysis of new Andean textile models. This was also the period during which Klee taught courses exclusively to members of the Weaving Workshop, including Anni Albers. It was Albers who most successfully synthesized Klee's lessons with what she was learning from studying actual weaving examples, Andean textiles among them. More than any other ancient example, Andean textiles served as useful counterpoints to Klee’s design theories and practices.

From the later Dessau Bauhaus period, under the direction of architect Hannes Meyer, and from 1930 until the Bauhaus permanently closed in 1933, under the direction of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, the Weaving Workshop was a place where art was almost exclusively produced according to social needs, due particularly to the school’s anti-pictorial and anti-art stance. Anni Albers received her Bauhaus diploma in February of 1930, but she continued her contact with the Weaving Workshop, serving as acting director of the workshop in 1931. Probably due to Albers, the Andean textile model provided the weavers with actual physical information that they needed in order to translate their ideas regarding production, construction, and utilitarianism into the domain of weaving. Interestingly, this was also a period when the handwoven product was highly valued at the Bauhaus, no longer as an individual expressionist statement but as an example for production. For this reason, because of the emphasis placed on maintaining the relationship between process and product, the Andean textile paradigm was valued.

Albers played an important role in the Weaving Workshop during most of the Dessau period. Her association with the school continued to the end partly because Josef continued to teach at the Bauhaus until its doors were permanently shut in 1933. Anni Albers's important contributions involved her ability to unite a geometrically abstract visual vocabulary with corresponding constructive processes, such as double and triple weaves, and also her creation of innovative weaving constructions, such as open-weaves and multi-weaves, so as to apply them to industry. She synthesized what she had learned from contemporary sources such as De Stijl, Paul Klee, and Constructivism and then applied these lessons to those she was learning from the Andean textiles.

_crop.jpg?w=245&h=163&c=1)

Kopie.jpg?w=245&h=163&c=1)