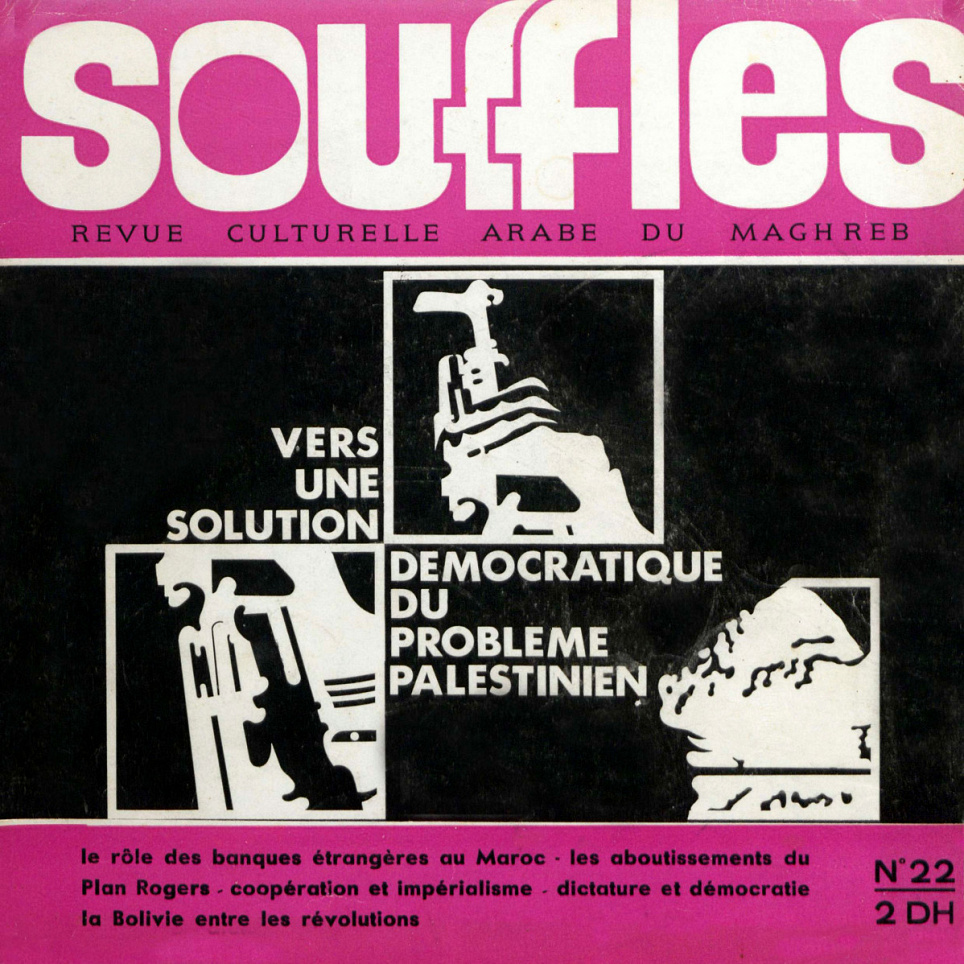

Souffles functioned as a node, medium and interface in the intellectual, political and artistic production of a nascent Moroccan postcolonial subjectivity. The editors of the magazine—a group of outstanding young writers, including Laâbi, Mostafa Nissaboury and Mohamed Khair-Eddine, decided to self-publish a literary magazine in 1966, ten years after Moroccan independence. As Laâbi stated in a conversation held in Paris in 2015, it was the colonial condition itself that shaped the counter narrative and radical outline of the magazine and its post-colonial aesthetics:

"First there was an understanding that we could not move forward without having resolved our problems with the colonial experience. The generation that preceded us, Moroccan men and women, was preoccupied with the political fight against the colonial system. That generation succeeded, as Morocco was able to regain its independence in 1956. But that generation never asked itself the question of whether colonization was a loss of autonomy and national dignity, or if it was a loss of something else. What happens in a colonial situation? Is it simply … political oppression, economic? Or is it something else? It was my generation that concretely asked itself about these problems. What happened culturally? What was the colonial enterprise in the framework of culture? What was the impact of colonial politics on the being, on the psychology of Moroccans, on their identity, on the relationship they have with their past, present, and future?" 2

2.

The anti-colonial struggle was successful in achieving political independence for Morocco, but ten years later young intellectuals confronted a situation where the colonial attitudes, as well as the socio-political structures of colonial governance, remained in place. It is thus telling that in one of its first editions, the Souffles editors conducted a conversation with the Tunisian-Jewish author Albert Memmi, who in his book, The Colonizer and the Colonized, analyzed the mental and cultural impacts of European colonization.3 The hybrid and transnational character of Souffles also relates directly to one of the main subjects of debate in its pages: the deep and abiding concern of artists and intellectuals with the awkward position for aesthetic production occasioned by both the colonial past and the conservative politics of many postcolonial regimes, including feudal oligarchies and ruling political parties. The central proposition of the magazine’s founders was the decolonization of society and culture had yet to take place—they made this their project. One of the striking feature of this “auto-decolonization” project, as Abdellatif Laâbi stated, was the experimental, deconstructive treatment of the French language:

"How to decolonize minds? How to decolonize culture? How do we rediscover our autonomy, our freedom of creation, in relation to a culture that was imposed upon us? But with this paradox: all of that must happen in the language of the colonizer; a paradox, a contradiction. It was necessary to deal with this paradox and this contradiction. How to produce a literature that would carry this movement for the emancipation of the human being? We worked with the only language that we had at our disposal. We didn’t choose it. I didn’t choose to write in French—French was imposed upon me during a history that went beyond me personally. The important thing was to see what I did with this language. What did I succeed in creating within this language? How did I make this language my own?"4

The postcolonial, polyphonic use of French by Souffles authors marks one of its outstanding features as a literary magazine. Their writing embraces the multiplicity and mixture of the language, emphasizing the diversity of tones, pronunciations, meanings and dialects expressed in spoken French. The contextualization and decontextualization of language and speech acts associated with the former French colonial school system thus constituted one major task for the young writers. Khair-Eddine speaks even of the formation of the Souffles authors as a “linguistic guerrilla.”5 Written French is moulded, appropriated and deconstructed; disruptions are introduced and new narrative forms are developed. The multilingual condition and pluralistic, cosmopolitan position of the magazine’s founders, including their interest in diverse narrative formats, gave rise to a number of language experiments, creolizations, and new literary forms.6 The experimental and imaginative handling of language is expressed in so-called poèmes kilométriques and other new forms of prose. The radicalization of narratives by means of montage and collage, techniques of fragmentation, non-linear narrative forms and an emphasis on language’s event-based character in the magazine can be read as a conceptual response to the rule of violence and the cultural paternalism of French colonial power. As Laâbi states, there was no model to build on:

"How to create a new literature? A literature that carries the mark of our memory, of our personality, our subjectivity. I believe that what was created with the journal Souffles was a sort of rupture, a sort of forward flight. We rejected the models that existed at the time, whether that be the Western literary model or the Arab literary model, the Near East. We had to invent our own model. And therefore, inevitably, there was a very violent split at that time. It was necessary to go forth into the unknown. We took a leap into the unknown, maybe not exactly entirely consciously. It was an urge that led us to make this jump into the unknown."7

A separate series published in parallel to Souffles called Éditions Atlantes, brought out important novels written by members of the editorial board, as well as befriended Algerian, Moroccan and Tunisian authors, creating a new platform of experimentation between writers of different nationalities and cultural backgrounds.

3.

Cultural conditions at the time of the first edition of Souffles were far from satisfactory in Morocco, necessitating self-organization and group-making. According to the art historian, poet and supporter of the Souffles enterprise, Toni Maraini, the postcolonial artists were responding to a post-independence condition in which a petty provincialism and Eurocentric culture based on academic fine art education still predominated:

"The salons organized for Western artists admitted only Moroccan “naïve” painters as a touch of "indigenous color." Local European poets used to gather in clubs littéraires around the foreign cultural missions “where they wrote verses on the ambassadors' gardens.” They ignored the best of Western production and the daring experiments of modernism, as well as the high tradition of classical Arabic poetry, not to mention Afro-Berber popular arts and literature. They were not interested in the productions of a Moroccan cultural avant-garde."8

At this time, Laâbi had begun publishing in several French literary magazines, but had become aware of a group of young Casablancan poets centered around Nissaboury and Khair-Eddine, who published small reviews in Poésie toute and Eaux vives. Here he also encountered the Casablanca Group of painters—Mohamed Melehi, Mohamed Chabaâ, and Farid Belkahia—who had studied in Czechoslovakia, the United States, Italy and Spain, and who came back to Morocco “with a diverse set of perspectives and skill sets, and … were on that same quest for modernity that we poets were on.”9 Constituted within this interdisciplinary set of relationships, the Souffles project commenced. Along with writers associated with the magazine, the artists also worked following the imperative to formulate a new aesthetic that would transcend colonial cultural production and the European episteme. Such a project also demanded a rethinking of established forms of cultural production in order to create a cognitive map of radical counter-proposals:

"When we revolted against the Western models, the Orientalizing models, we aimed to create our own concepts, something of the future. Of course, at the time, we found some intellectuals, some creators, who helped us in this process: Frantz Fanon, who went very far, in a clinical way, to analyze the colonial phenomenon as it happened and its repercussions on the identity of peoples and their cultures. Aimé Césaire, of course, an important poet, who was at the time one of our older brothers. And other poets who were kicking at the stalls as they say. Vladimir Mayakovsky was one of these, for me anyway. Russian poetry from the 1920s and 30s, not just Mayakovsky and futurists such as Velimir Khlebnikov, among others, but also the Turkish poet—whose engagement was not only in writing, but also in politics—Nâzım Hikmet. A poet who paved the way by demonstrating that poetry could be very dangerous, but that it was necessary to accept this danger…"10

_crop.jpg?w=245&h=163&c=1)

Kopie.jpg?w=245&h=163&c=1)