The Bauhaus and the Tea Ceremony

Cover of Kenchiku Kōgei (Architecture and Design)

I SEE ALL, Tokyo: Koyo-sha, 1931–36, Private Collection

(Prof. Dr. Hiromitsu Umemiya).

Introduction

The impact of Bauhaus teaching methods, particularly Johannes Itten’s (1888–1967) preliminary course, has been lasting and extensive. In the 1920s and 1930s, Germany possessed one of the most progressive art scenes in the world. Avant-garde groups and galleries, as well as the Bauhaus and other similar art schools—such as the Itten-Schule and Reimann-Schule—appealed to large numbers of international students, including from Japan, creating a transnational network of artists, architects and designers. This article will analyze the mutual impact of design education between Germany and Japan in order to shed new light on the tightly knit network of associations that developed between Japan and Europe in the interwar period.

Lecturing in Japan in 1936, the architect, urban planner and author Bruno Taut (1880–1938) commenced his talk Fundamentals of Japanese Architecture with the statement that “the exotic no longer exists in Europe for Japan, or in Japan for Europe.”1 In other words, in the period between the two world wars, Japan had already lost the connotation of exoticism it had once possessed; interest in its culture had become relatively commonplace. During the 1920s and 1930s, Japanese artists took an active role in artistic dialogue internationally, and members of the intelligentsia contemplated Japanese aesthetic and philosophical ideas throughout the world.

The foundation of the contemporary avant-garde in Central Europe comprised a combination of diverse sources such as the British Arts and Crafts movement and Japonisme.2 The “oriental” or Japanese element in modern design promoted by the Bauhaus and other modernist institutions in the interwar period has as yet not been studied in sufficient detail, nor do scholars reference primary Japanese sources in their work, giving a distorted picture of the cross-fertilization that existed between the European and Japanese cultural milieus of the period. In the context of the Bauhaus and like-minded progressive schools, the Japanese element was evident in ink-painting exercises, principles taken from calligraphy, principles of Asian religious philosophy and cultural practices such as the Japanese tea ceremony. Japanese students enrolled in the Bauhaus noted their uncanny response to Bauhaus modernist architecture, so strongly reminiscent of Japanese traditional architecture and the aesthetics of tea culture. (It is worth noting that the understanding of tea culture and teaism was communicated to Euro-America years before the Bauhaus was founded through the work of art curator and thinker Okakura Kakuzo (1892–1913); in particular, through his well-known treatise, The Book of Tea.3)

The prevalent approach when examining the European avant-garde and its relationship with Japanese artists and designers has been to explore the unidirectional “influence” of European schools such as the Bauhaus on Japan. This study offers a new perspective, emphasizing mutual transnational exchanges within a network of progressive educational institutions located in both Europe and Asia. It also maps the activities and enthusiasms of expatriate Japanese artists in Berlin and other Central European cities that so far have received relatively little scholarly attention. This research reveals how Japanese visitors to Europe provided a direct channel for promoting the Bauhaus style in Japan. It did not take long for several schools to be founded based on the dissemination of these artistic and pedagogical influences, including Jiyu Gakuen (School of the Free Spirit) and the “Japanese Bauhaus” in Tokyo (Seikatsu Kosei Kenkyusho (Research Institute for Life Configurations): later renamed Shin Kenchiku Kogei Gakuin [School of New Architecture and Design]), founded in 1931 specifically to adopt Bauhaus methodology to the Japanese context.4 This process had significant cultural as well as political implications.

In Japan the devastation to the Tokyo urban landscape by the Great Kanto Earthquake in 1923 is considered a turning point in Japanese modernism, and, in fact, might be considered its true starting point. The disaster provoked the concrete realization among Japanese urban planners and architects that a modern style of building was needed for Tokyo’s emerging modernist urban culture. One of the earthquake’s rare survivors was the Imperial Hotel (1923) designed by Frank Lloyd Wright.5 Concurrently, the interwar period saw the establishment of several new states on the European continent: changes to Europe’s map gave rise to new artistic centers. In addition, dynamic advances in technology dramatically changed methods of communication, making the relationship between centers and peripheries far more fluid and malleable, both nationally and internationally. Arguably, such technological transformations also contributed to the frantic transnational dialogue of artists in the period, in many cases significantly impacting their creative process. One aspect of this fairly ubiquitous phenomenon, especially evident in Central Europe, is that the intellectuals who participated in such transnational dialogues often possessed multiple national and cultural identities.

Erich Consemüller, Balance study from the Bauhaus preliminary course with Josef Albers, ca. 1927, Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau (I 46263/1-2), © Dr. Stephan Consemüller.

The Bauhaus (1919–1933) was conceived as a modern art and design school, epitomizing the modernist approach—functionality, simplicity of form, and the use of modern materials. The school quickly established its place within the design landscape as a center for new practices in art and culture, using form to introduce order to life. Not long after its founding, the Bauhaus became the center of an international modernist network; a model for many artists in Europe and America.6 While it may have possessed rigid rules and fixed ideas, its success lay in how it concentrated exceptional individuals in one place. Under the umbrella of unity and integrity, the individual approaches to teaching and creativity of the three Bauhaus directors and faculty (Meisters in Bauhaus terms) varied. Expressions such as Bauhaus style and Bauhaus pedagogy are clichés: there was little uniformity or continuity from one director to the next. Nonetheless, despite variations in styles and modes of conceptualizing, the presence of a Japanese element remained significant. Inspiration from Japanese art and culture was present at the Bauhaus from its foundation to its closure, interwoven within the rich tapestry of Bauhaus creative activities. The Bauhaus’s Japanese quality has roots in the wave of Japonisme that had exerted a profound influence on previous generations of European and American artists for well over half a century. A certain superficially obvious Japanese quality to Bauhaus design is thus better understood as the concentration of a tendency permeating the personal work of artists active at the institution and encouraged as well within its overall pedagogical program.

Johannes Itten, the artist and teacher who first drafted the modern and innovative teaching methods at the Bauhaus, was possessor of an eclectic combination of interests, including a preoccupation with Asian art and ideas, typical of the most progressive circles of European art and culture. The son of a teacher from rural Switzerland, he was invited to Vienna in 1916 to set up an art school where he could fulfil his ambitions as both artist and instructor,7 providing an outlet for his concern with the need to balance outward-oriented thinking with internal spiritual growth. Itten believed there was no difference between an artist and craftsman—an artist for him being merely a more intense craftsman—thus his teaching was guided by practical instruction while also inspired by the vogue for mysticism that had reemerged after the war, when Christian mystics such as Meister Eckhart and Jakob Böhme, as well as the teachings of the Buddha and Lao-Tzu were widely read.8 In 1919, he was invited to Berlin to help Walter Gropius (1883–1969), the architect and founding director of the Bauhaus, establish the teaching structure and methodology of the Bauhaus. Gropius himself was inspired by the British Arts and Crafts movement’s desire to resuscitate aspects of the Medieval craft guild system, and his plan for the Bauhaus, promoted under the motto Art and Technology—a New Unity, entailed teaching all subjects under one roof, with students spending equal time in theoretical lectures and practical workshops.

Itten’s main task was to create a Vorkurs (preliminary course), obligatory for all Bauhaus students,9 an innovation that was to gain broad influence outside Germany. Itten established three objectives for this course, subsequently followed by his successors: to develop creative abilities and artistic potential free from all conventions; a thorough knowledge and feeling for materials gained through personal experience; and to learn the basic rules of artistic creative process, including color and form theory.10 In explaining the rhythm of the brush and composition, Itten drew on examples from Japanese and Chinese ink paintings, especially from the Nanga School (“literati painting,” from the Japanese nanshūga), southern style painting—also termed Bunjinga (“scholar painting”)—and the calligraphy and artwork of Zen Buddhist monks.11 Zen paintings were, in his opinion, an ideal example of art that operated through spiritual rather than formal values. Itten made his students draw abstract feelings, moods, weather conditions and seasonal ambiances. In fact, he did not teach mimesis but rather encouraged his students to search for a sense of unity with the painted object. Perhaps based on Itten’s activities, Claudia Delank concluded that “it is safe to state that the eyes of the Bauhaus student were trained in a Far Eastern painting.”12 The impact of Itten’s preliminary course has been considerable. To quote Henry P. Raleigh: “Today, there is barely an art program at any level of education that does not, in greater or lesser degree, contain some remnant of the old preliminary course.”13

Erich Consemüller, Material and construction study from the Bauhaus preliminary course with Josef Albers, ca. 1927, Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau (I 46271/1-2), © Dr. Stephan Consemüller.

Vital creativity and spontaneity of expression were not the sole preserve of the masters; their presence at the Bauhaus was also due to the great diversity and cosmopolitan nature of the Bauhaus students, which included a colorful group of talented novices, graduates from fine art schools throughout Europe and established artists. Although the sudden closure of the Bauhaus in 1933 meant only a few Japanese students actually attended the school, Bauhaus ideas generated great excitement in Japan. In 1922, the architect Ishimoto Kikuji (1894–1963) and the artist Nakada Sadanosuke (1888–1970) arrived at the gates of the Bauhaus in Weimar, where Nakada enrolled as the first Japanese student.14 Upon his return to Japan in 1925, Nakada wrote an article for the magazine Mizue entitled “The State Bauhaus” from which many students drew inspiration. Yamawaki Iwao (1898–1987), an architect who together with his wife Yamawaki Michiko (1910–2000) studied at the Bauhaus for two years in the early 1930s wrote: “Young Japanese architects were fighting to buy, for example, vol. 14 of the Bauhausbücher Von Material zu Architektur by Moholy-Nagy in 1929.”15 Iwao and Michiko arrived in Germany in 1930, entering the Bauhaus in Dessau as the 469th and 470th student respectively. Although Yamawaki Michiko would later claim that she had no interest in design prior to meeting Iwao, her sensibility was informed by her refined upbringing in the elegant family home where her father maintained a tea ceremony practice. This formative milieu resonated with her subsequent experience of the Bauhaus and the modern art she encountered in Germany.16

What was their experience like? Lectures were taught in German, which was not easy for Michiko whose knowledge of the language was basic at the time. In her book she gratefully notes that Josef Albers (1888–1976) and Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944) were kind enough to devote extra time to both Yamawakis after class, explaining difficult parts of their respective lectures in English.17 Iwao recalled the time Kandinsky piled up various objects belonging to students, including chairs and even muddy bicycles, urging his pupils to concentrate on the assemblage until they were able to see simple shapes—what he termed the Spannung (tension) of form. She remembered Albers being especially kind, noting that his appearance was reminiscent of someone who performed chanoyu (tea ceremony).18 She claimed the Bauhaus was very similar to the way of tea in its appreciation of and esteem for simple and functional things, and its effort to foster the natural material quality of things.19

Due to the closure of the Dessau campus in 1932 by the city municipality the Yamawakis could not complete their degrees. They elected to return to Japan instead of continuing in Mies van der Rohe’s (1886–1969) privately operated Bauhaus in Berlin. An article about the Bauhaus closure in 1933, published in the magazine Kokusai kenchiku (International Architecture), was illustrated by what is probably Iwao’s most famous work, the photomontage Attack on the Bauhaus from 1932 (a work he could not exhibit in Germany), which anticipated the Gestapo’s final closure of the Bauhaus by a year.

In this period, two other Japanese students studied at the Bauhaus, although not much is known of their experiences there. The architect Yamaguchi Bunzo (1902–1978) was one, as was textile designer Ono Tamae (1903–1987), perhaps the least known of the Bauhaus’s Japanese students. Born in Nagano prefecture, Ono traveled with her husband Ono Shunichi to Berlin, where the couple lived from May 1932 to October of the following year. During her stay she studied at the Bauhaus weaving atelier. Her works, mainly woven carpets, were accepted eight times by the official Nitten salon exhibition. The Nitten salon (Nihon Bijutsu Tenrankai or Japanese Art Exhibition) evolved from the Bunten (Monbusho Bijutsu Tenrankai, or Ministry of Education Art Exhibition). Modelled after the French Salon, it was established by the government in 1907, with categories for Nihonga (Japanese style), Yoga (Western style) and sculpture sections. The Bunten provided Japanese artists with an opportunity to compete on a national level, while also increasing the general public’s consciousness of art. Exposure at the Bunten and, subsequently, at the Nitten was associated with social prestige, which intensified pre-existing rivalries among different groups of artists. Before attending the Bauhaus, Ono had studied with the painter Nakagawa Kigen (1892–1972). Nakagawa himself had studied with Henri Matisse while living in Paris between 1919–1921. For the rest of her career Ono remained indebted to Nakagawa and his abstract work. Perhaps Ono has so far eluded many researchers focused on the Bauhaus and Japan because she studied at the Bauhaus for only four months. Her work, however, was included in a 1994 exhibition at the Kawasaki Art Museum, The Bauhaus Revolution and Experiment in Fine Arts Education.

Ginza Japanese Bauhaus building, School of New Architecture and Design, 1930s, Private collection.

To return to the Yamawakis: upon their return to Japan, the couple joined social circles promoting a modern, Euro-American lifestyle. They lectured widely in both formal and informal settings (Nakada Sadanosuke’s apartment being one example of the latter). With help from Michiko’s father, the Yamawakis settled in an apartment in the newly-built Tokuda Building in Ginza district, designed by Tsuchiura Kameki (1897–1996). The couple rented accommodations taking up the third and half of the fifth floor. In the latter, two looms were installed (Michiko having studied in the Bauhaus weaving workshop under the supervision of Gunta Stölzel [1897–1983] and Annie Albers [1899–1994]). In this fifth-floor space, the couple also housed a collection of books, objects designed at the Bauhaus and even simple furniture from the school canteen, so that the studio served the Yamawakis as a location to reconstruct the Bauhaus atmosphere and its pedagogical teaching methods in Japan. In time, this studio became an important meeting point. Frequent guests included the photojournalist Natori Yōnosuke (1910–1962) and Kawakita Renshichirō (1902–1997), founder of the “Japanese Bauhaus.” He invited the couple to teach in his school, the Shinkenchiku kōgei gakuin (School of New Architecture and Design), located in the Mitsuki building in Tokyo’s Ginza district. In 1934, the school added new courses to its curriculum. Michiko became head of the weaving course, and her colleague Kageyama Shizuko was chosen to lead the Western fashion design department. Both courses were advertised in the contemporary women’s magazine Fujin gahō as part of a newly formed Center for Weaving and Fashion Design. Iwao was also active as a teacher from 1949 until his retirement in 1971, incorporating concepts learned from Josef Albers and Wassily Kandinsky20 at both the Nihon University College of Arts and the Tokyo University of Education, antecedent of today’s Tsukuba University. Both Michiko and Iwao published separate account of the Bauhaus; Michiko with Bauhausu to Chanoyu (Bauhaus and Tea Ceremony) and Iwao in 1954 with Bauhausu no Hitobito (People of the Bauhaus). Previously he had published a reflection on his work, the Bauhaus experience and photography under the title Keyaki (The Zelkova Tree). An expanded version published thirty years later included a number of essays on aesthetics, modern design, architecture and the legacy of the Bauhaus under the title Keyaki zoku (The Zelkova Tree Series). Michiko, with her formative childhood experience of tea culture, was well placed to convey the Japanese quality she later encountered at the Bauhaus—where she felt she had re-entered the world of tea, with the concept of the tea ceremony aesthetic resonating within the idea of the contemporary Modernist Gesamtkunstwerk—publishing her memories of the school in a book edited by graphic designer and design historian Kawahata Naomichi. Here she offered detailed insights into the Bauhaus, in particular, her affinity with the Bauhaus ideas of simplicity, functionality and the school’s deep interest in materials, their quality and use—as well as the world of modern “boys” and “girls,” the so-called mobo and moga of 1930s Tokyo.21

Through Michiko Yamawaki’s account of the Japanese quality of the Bauhaus, we return to Germany and Johannes Itten’s activities upon his departure from the Bauhaus. In 1923, Itten returned to the Swiss town of Herrliberg. Three years later, he returned to Germany, exhibiting at Herwarth Walden’s gallery Der Sturm. In September 1926, he founded the Moderne Kunstschule Berlin, whose curriculum aimed to teach a wide range of artistic practices, developing the individual creativity of the students through modern methods. Many of the school’s teachers were from the Bauhaus: Georg Muche, Umbo, Fred Forbat, Friedrich Köhn, Lucia Moholy. Exhibitions featuring works by Bauhaus students and teachers further strengthened the link between the two schools: Walter Gropius was often a panel member during architecture examinations. The school was heavily promoted in the press, and exhibitions of students’ work travelled around Germany in the early 1930s. The scholar Kaneko Yoshimasa has written in great detail about the Itten-Schule and its contacts with Japan, one of his main sources being the diary of Johannes Itten from 1930–31, currently held at the Kunstmuseum Bern. Kaneko further clarified the relation between Itten-schule and Japan, such as the activities of some Japanese, such as Mizukoshi Shōnan, Obara Kuniyoshi, Alekisan(Alexander) Nagai, Takehisa Yumeji, Yamamuro Mitsuko, Imai (Sasagawa) Kazuko and Eva Plaut that will be discussed briefly later. In one series of diary entries, Itten reports on the visit of a Japanese delegation to Europe, including three painters—Komuro Sui’un, Mizukoshi Shōnan and Hiroshima Koho—who had traveled to Berlin for the Contemporary Japanese Painting Exhibition (Ausstelung von Werken Lebender Japanischer Maler), held in January and February 1931 at the Prussian Art Academy. Mizukoshi Shōnan (1888–1985) gave several lectures at the Itten-Schule on the subject of ink painting—mainly that of the nanga school22—and also spoke at the house of the commercial attaché of the Japanese Embassy, Alekisan (Alexander) Nagai, himself an amateur painter and active promoter of Japanese art, who served in Berlin until the end of the Second World War.23 The Itten-Schule was also visited by Obara Kuniyoshi (1887–1977, the education reformer and founding director of the progressive Tamagawa Gakuen School,) during a study trip he arranged to Europe and America. Obara attended Mizukoshi’s lectures at the Itten-Schule, noting in particular his attempts to explain how to paint the “essence” of the object, that the whole picture should have a rhythm as in music. Obara also relates that Mizukoshi was hired to teach ink painting at the school for six months, teaching the subject in a uniquely philosophical manner characteristic of the Nanga school.24 During his time in Berlin, Itten also hired Mizukoshi to be his private teacher, as Itten recounts in his diaries.

Study at the Itten-Schule was divided into two parts, a preparatory course and a specialist course that students could enter only after finishing the introductory course. According to the curriculum of 1932–33, the preparatory course included principles of light and dark, contrast theory and Sino-Japanese method of brush painting, a subject added to the curriculum following Mizukoshi’s departure.25 As at the Bauhaus, the daily routine at the school commenced every morning with thirty minutes of physical exercise and singing—in order to harmonize body and mind—followed by thirty minutes of free painting with brush and ink (sumi-e).26 This morning routine was intended to prepare students for the rest of the day. Itten put great emphasis on regular breathing practice in the hope they would help students identify with plants and grasses. Taken together, these practices point towards the profound influence of the Japanese ink-painting tradition on pedagogical method employed at the Itten-Schule. On another occasion at the Japanese embassy, Itten met another painter, Takehisa Yumeji, employing him at the school from February to June 1933. Yumeji published two texts during his stay, translated into German by Alexander Nagai— “The Concept of Japanese Painting” (Der Begriff der Japanischen Malerei) and “On Lines” (Über die Linien). These were devoted to an array of subjects, from a general exploration of Japanese culture, to a comparison of European and Japanese painting, as well more specific issues, like the role of emptiness in Japanese painting.27

By the mid-1930s, the most influential art schools in Japan, such as Tokyo University of the Arts, had projects originating in various Bauhaus workshops.28 According to the scholar Suga Yasuko, design or kōgei played an important role in creating a Japanese national identity in the twentieth century, and in a separate but related development, issues concerning feminism and gender also entered into public discussion at this time.29 These tendencies, together with the revived interest in Japonisme in Europe and the United States, jointly allowed for new opportunities within the development of Japanese design. One manifestation of this confluence of social and aesthetic trends in Japanese society was the Frank Lloyd Wright designed Jiyū Gakuen, established in 1921 by Hani Motoko (1873–1957), a tireless Christian activist and the first female journalist in Japan. After Obara Kuniyoshi’s visit, the Itten-Schule strengthened its ties with Japan generally, especially with this Jiyu Gakuen school. In 1932, Jiyū Gakuen students came to study at the Itten-Schule.30 After the school established an affiliated design research institute, two students of the department, Imai Kazuko and Yamamuro Mitsuko, traveled to Europe for eighteen months to gather new perspectives on teaching modern design, arriving in Prague in 1931 and settling there for half a year.31 Yamamuro enrolled at the Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design, taking classes with Jan Beneš, who taught drawing and painting. Dissatisfied, she resigned from the school on 1 March 1932. Imai also found the Prague Academy too traditional. Each wrote back to the college that, like Japan, Czechoslovakia had yet to produce designs appropriate for modern times. Subsequently, the two women travelled to Vienna, visiting Josef Hoffmann, then continuing on to Budapest, Frankfurt, Munich and Halle before arriving in Berlin, where they made contact with the Yamawakis, their intention being to enroll at the Bauhaus. However, due to administrative issues they decided to study at the Itten-Schule instead.32

Study at the Itten-Schule was dramatically different from the overly academic style of teaching the two women had encountered in Prague. Itten, an aficionado of Japanese art, stayed in touch with the two women following their departure, remaining very influential to Imai and Yamamuro after their arrival back in Japan.33 Imai bought a copy of Itten’s published diaries, using its contents in her teaching: it might be said that his novel pedagogical method, created by merging psychology and philosophy with “oriental” philosophies and religious teachings, came full circle by being put to use in Japanese classrooms. Imai also attended the Reimann-Schule, founded in 1902.34 Unlike the Bauhaus and the Itten-Schule, the Reimann-Schule taught fashion sketching and drawing, shop window design and other commercial design skills. The school was very popular, especially among female students. For three months Imai attended classes at the Reimann-Schule every day after her lessons at the Itten-Schule,35 taking classes in stage design, textiles and commercial window display. She was impressed by how the school treated a “product” as if it were a craft or design piece—an idea later promoted at Jiyū Gakuen.36 Imai and Yamamuro visited the Bauhaus several times, once accompanied by Jiyū Gakuen founder Hani Motoko and her daughter Keiko. Students Ruth and Eva Kayser befriended Yamamuro and Imai at the Itten-Schule. Ruth kept in touch with both women, and in a letter dated 14 July 1933, wrote that she had learned a lot from Takehisa Yumeji and his lectures.37 Eva Plaut, who studied at the Itten-Schule between 1932 and 1934 and later taught at the Sorbonne, was also inspired by Yumeji’s lectures, claiming his teaching methods inspired her in becoming a teacher.38

Cover of Kenchiku Kogei (Architecture and Design) I SEE ALL, Tokyo: Koyo-sha, 1931–36, Private Collection (Prof. Dr. Hiromitsu Umemiya)

Kawakita Renshichiro and New Bauhaus in Tokyo

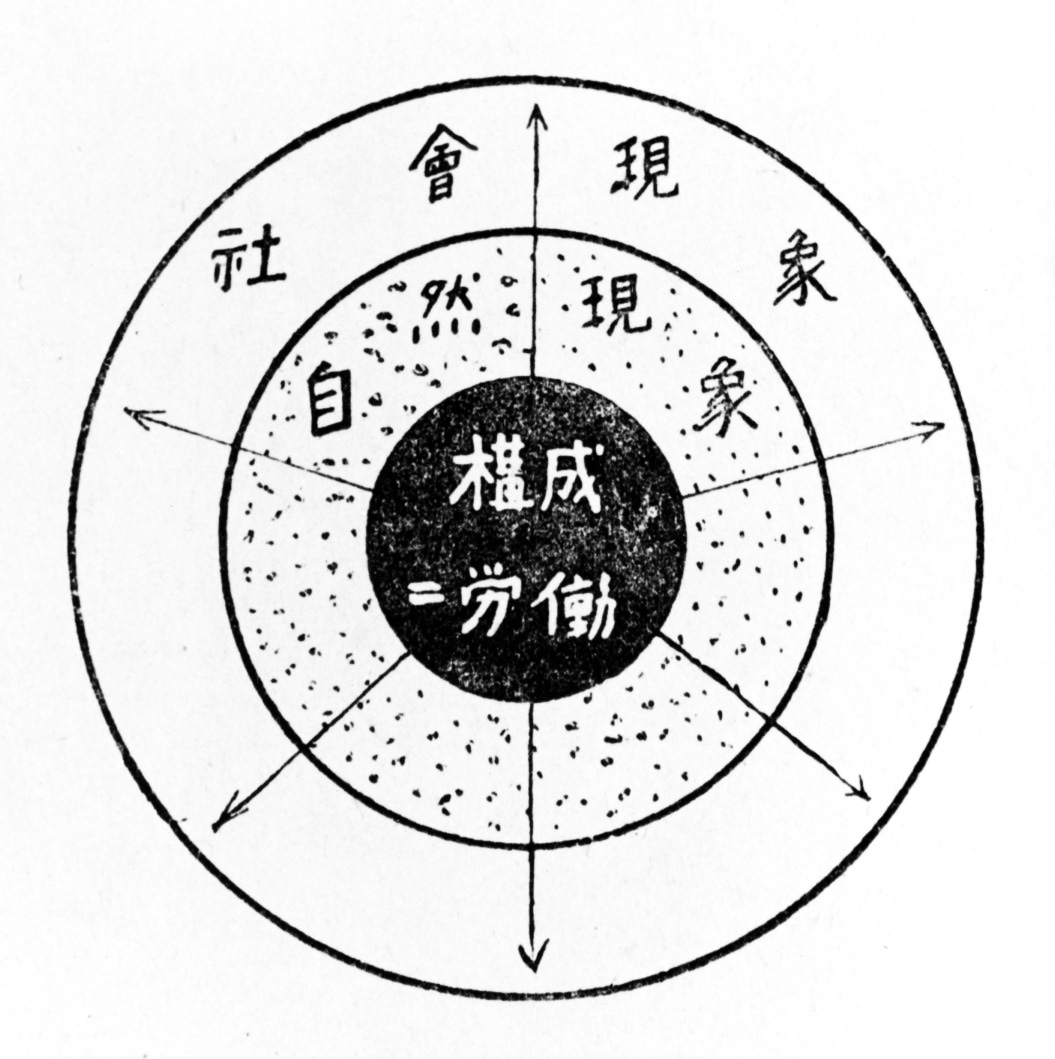

Upon their return to Japan, Yamamuro and Imai—like many other Japanese students who attended the Bauhaus and related institutions—made contact with Kawakita Renshichiro, who invited them to lecture on Itten’s method at his school.39 Both were surprised to find the extent of the overlap between Japanese and European art practice, sharing this information with Yamawaki Michiko. Beginning in 1931, upon opening his first attempt at creating a Bauhaus-influenced design school, Seikatsu Kōsei Kenkyūsho (Research Institute for Life Configurations), Kawakita began translating many of the texts the Yamawakis brought back from Germany to use as teaching material at his school, including László Moholy-Nagy’s Von Material zu Architektur (From Material to Architecture). A central figure in the history of the diffusion of Bauhaus-inspired ideas in Japan, Kawakita was born in Tokyo in 1902. He graduated from the Architecture department of the Tokyo Institute of Technology, and in 1930 received fourth prize in the international competition for the design of the Ukraina Theatre in Harkow. Kawakita had been fascinated by the Bauhaus even before meeting the Yamawakis, especially Kandinsky’s musical visuality, which he drew upon in his architectural practice during the period 1924 and 1927. (He was also inspired by Walter Gropius’s book, International Architecture, whose influence was at its height around 1928, and by the search for commonality between different regional architectural styles. Hannes Meyer’s ideas of architecture as founded on scientific research methodologies was also profoundly influential.) A close friend of other students who had visited the Weimar Bauhaus in the 1920s, he founded Seikatsu Kosei Kenkyusho together with two former Bauhaus students, Mizutani Takehiko and Nakada Sadanosuke. Kawakita also began publishing a magazine, Architecture and Design, I See All, in November of the same year, using it as a platform to broadcast ideas about international architecture and urban lifestyle in Japan, as well as to publicize his institute. In 1932, he founded the Shinkenchiku kōgeika (Department of Modern Architecture and Design) department in the School of Industrial Design, led by the influential graphic designer, Hamada Masuji. When Hamada’s school moved out, he opened the Shinkenchiku kogei gakuin (School of New Architecture and Design). The school was progressive, basing its curriculum on the Bauhaus. Kawakita employed many of the “Japanese Bauhaus” students, including the Yamawakis. Among its graduates were the pioneering designer Kuwasawa Yoko (1910–1977), and the graphic designer Kamekura Yūsaku (1915–1997), who later became famous for his design work on the 1964 Tokyo Olympics and the 1970 Expo in Osaka. Like the Bauhaus itself, the school was fairly short-lived: the Ministry of Education refused to grant it a permit. Amid the rising fervor of Japanese militarism, it was forced to shut down in 1936. And as with the Bauhaus, the connections between Shinkenchiku kogei gakuin and other institutions abroad, along with its foreign ethos, appeared suspicious to the increasingly nationalistic regime. But its long-term cultural impact in Japan was indeed profound.

Concluding Remarks

This study has aimed to show the complex network of institutions and individuals circulating between Japan and Europe in the interwar period. Progressive schools such as the Bauhaus played a major role in the transformation of the artistic scene and the development and creation of Gesamtkunstwerks in different fields. This latter aspiration is reflected in works by Yamawaki Iwao, in Kawakita Renshichiro’s theory of design education and even in Walter Gropius’ office at the Bauhaus itself. Furthermore, places such as the Bauhaus, the Itten-Schule, and in broader terms, the city of Berlin itself all became transnational hubs and crossroads. As noted in the above, the newly nuanced sensitivity towards “things Japanese” (Japonisme) formed the underpinnings of a new transnational network that actively supported avant-garde activity in both Germany and Japan. This study has mapped a fragment of this network, focusing on progressive educators such as Johannes Itten, Obara Kuniyoshi and others. Additionally, this transnationalism can be seen represented in the life and work of Yamawaki Michiko, who sensed the Japanese atmosphere and elements in the Bauhaus’s teaching methodology, its spirituality and values, which she compared, as noted previously, to one of Japan’s traditional arts—the tea ceremony. This transnational experience was fundamental to Michiko becoming a progressive weaver not solely beholden to modernist paradigms. Rather, her work and life displayed a hybridity in which elements from both Japanese and Euro-American tendencies found expression. This aspect of her work is indicative of the kinds of cross-fertilizations that fed many other artists, designers and architects of her generation. This transnational aspect of Michiko’s career, similar to that of many other artists at the periphery of the mainstream modernist narrative, has been marginalized for decades. My taking up a transnational approach based on researching multilingual sources has proved fruitful in bringing evidence of the mutuality of the relationship between Japanese and European creators and pedagogues that the Bauhaus helped to foster. With this text I have attempted to open up an area of research that still suffers from a lack of translation and cross-cultural communication in the hope that others will follow.

Further references

- John E. Bowlt, “Constructivism and Russian Stage Design,” in: Performing Arts Journal, Vol. 1, No. 3, 1977, pp. 62–84.

- Helena Čapková, “Transnational Networkers—Iwao and Michiko Yamawaki and the Formation of Japanese Modernist Design,”in: Journal of Design History, Vol. 4, 2014, pp. 370–385.

- Walter Dexel, “Bauhaus Style—A Myth,” in: Eckhard Neumann (ed.): Bauhaus and Bauhaus People. Personal Opinions and Recollections of Former Bauhaus Members and Their Contemporaries, Wiley, John & Sons, New York 1992.

- Y. Fujita, “Orinifurete shonan sensei kara ukagatta o-hanashi kara (From a conversation with Master Shonan from time to time),” in: Miru News, Kyoto National Museum of Modern Art, 112, September 1976.

- Kazuko Imai and Mitsuko Yamamuro, “Prāgu yori,” in: Gakuen Shinbun, No. 7, 1931.

- Karl Lagerfeld, Iwao Yamawaki, Steidl, Göttingen 1999.

- Yoshimasa Kaneko, “A Study on the Art Education of Yumeji Takehisa at the Itten-Schule,” in: Daigaku-Bijutsukyoiku Gakkaishi, No. 33, 2001, pp. 143–150.

- Yoshimasa Kaneko, “Japanese Painting Lessons at the Itten-Schule,” in: Daigaku bijutsukyōiku gakkaishi, No. 25, 1993, pp. 247–256.

- Yoshimasa Kaneko, "Johannes Itten’s Design Education and Japan>," in: Journal of the Asian Design International Conference, Vol.1, 6th ADC (Asian Design International Conference) in Tsukuba, Japan, ISSN1348-7817, published in CD-ROM, 2003.

- Yoshimasa Kaneko: “The Relationship between Johannes Itten and some Japanese in Berlin,” in: Bulletin of Japanese Society for the Science of Design, Vol. 50, No. 6, 2004, pp. 1–10.

- Yoshimasa Kaneko, "A Study on the accepting process of the formative education from Ittenschule to Japan. -Based on the achievements of Mrs. Mitsuko Yamamuro and Mrs. Kazuko Sasagawa," in: Bujutsukyoikugaku, No.16, 1995, pp.85–99 (in Japanese).

- Yoshimasa Kaneko, "A Study on the Educational Relationship between Johannes Itten and some Japanese People. -With a Special Reference to the Activities of Shounan Mizukoshi and Kuniyoshi Obara," in: Daigaku-Bijutsukyoiku-Gakkaishi, No.32, 2000, 133-140, (This article was submitted to the Japanese Academic Society Daigaku-Bijutsu-Kyoikugakkai, on August 1999) (in Japanese with English summary).

- Yoshimasa Kaneko, "Jiyu-Gakuen students who studied at the Itten-Schule," in: Yasuaki Okamoto (Ed.), Johannes Itten Wege zur Kunst Ronbun-Schu (Academic articles collections), The special publication based on the conferences that were held during exhibition, Utsunomiya museum, 2005, pp.53–80 (in Japanese).

- Yoshimasa Kaneko, "Johannes Itten’s Philosophy of Human-Centered Art Education. –Contents Analysis of 'Tagebuch von Johannes Itten' based on a Conversation with Eva Plaut," in: Bijutsukoikugaku, No. 28, 2007, pp.143-155, p.444 (in Japanese with English summary).

- Yoshimasa Kaneko, "Johannes Itten and Zen," in: Christoph Wagner (Ed.), Esoterik am Bauhaus. Eine Revision der Moderne?, Regensburger Studien zur Kunstgeschichte 1, Verlag Schnell&Steiner GmbH, 2009, pp.150-172 (in English.

- Naomichi Kawahata, Kamekura Yūsaku, Transart, Tokyo 2006.

- Sadanosuke Nakada, “State Bauhaus,” in: Mizue, No. 6–7, 1925.

- Kuniyoshi Obara (ed.), Gakuen Nikki (College Diary), Tamawagagakuen, Tokyo 1931.

- Pamela Sakamoto, Japanese Diplomats and Jewish Refugees. A World War II Dilemma, Praeger, New York 1998.

- Yasuko Suga, “Modernism, Commercialism and Display Design in Britain. The Reimann School and Studios of Industrial and Commercial Art,” in: Journal of Design History, No. 19, 2006, pp. 137–154.

- Yasuko Suga, The Reimann School: A Design Diaspora, Artmonsky Arts, London 2014.

- M. Tsunemi, “Design Activities and Works of Bauhaus student Tamae Ohno,” paper presented at the Conference on Asia Society of Basic Design and Art, Tsukuba 2007.

- Hiromitsu Umemiya, “Kawakita’s 1930s,” in: Hiromitsu Umemiya, Modanizumu/ nashonarizumu, 1930 nendai nihon no geijutsu, Serikashobo, Tokyo 2003, pp. 102–132.

- Rainer K. Wick, Teaching at the Bauhaus, Hatje Cantz, Ostfijilden-Ruit 2000.

- H. Yamano (ed.), Yohanesu Itten: zōkei geijutsu e no michi (Johannes Itten, Wege zur Kunst), Kyoto Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto 2003.

- H. Yamano (ed.), Avant-garde in Japan—Art into life 1900–1940 (exhibition catalogue), National Gallery of Modern Arts in Kyoto, Kyoto 1999.

- Iwao Yamawaki, Bauhausu no Hitobito, Shokokusha, Tokyo 1954.

- Iwao Yamawaki, Keyaki, Atoriesha, Tokyo 1943.

- Iwao Yamawaki, Keyaki zoku, Nihon Daigaku, Geijutsu gakubu, Bijutsugakkakenkyushitsu, Tokyo 1973.

- 1 Bruno Taut, “Fundamentals of Japanese Architecture”, Tokyo 1936’, Lecture at the Peers’ Club, 30 October 1935.

- 2 Anthony Alofsin, When Buildings Speak. Architecture as Language in the Habsburg Empire and its Aftermath, The University of Chicago Press, London and Chicago 2006, p. 56.

- 3 Kakuzo Okakura, The Book of Tea, Fox, Duffield and Co., Boston 1906. Okakura’s ideas and writings had a far-reaching international impact, surpassing the direct circle of his American friends and admirers, such as Isabella Stewart Gardner (1840–1924), and inspired his counterparts in Asia, which he was keen to present as the center of the arts. One of them, Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941), said: “(Okakura) would often buy some very cheap things, like simple clay oil-pots that peasants use, with (an) ecstasy of admiration, some things in which we had failed to realize the instinct for beauty.” In: Rabindranath Tagore “On Oriental Culture and Japan’s mission,” Address to the member of the Indo-Japanese Association, Tokyo, 15 May 1929; The English Writings of Rabindranath Tagore, vol.3., p.605.

- 4 Rich research about Jiyu Gakuen school in the context of Bauhaus provided in Yoshimasa Kaneko’s articles as follows: Yoshimasa Kaneko, <A Study on the accepting process of the formative education from Ittenschule to Japan. -Based on the achievements of Mrs. Mitsuko Yamamuro and Mrs. Kazuko Sasagawa, in: Bijutsukyoikugaku, No.16, 1995, pp.85-99. Yoshimasa Kaneko, "Johannes Itten’s Design Education and Japan," in: Journal of the Asian Design International Conference, Vol.1, (6th ADC in Tsukuba, Japan), published in CD-ROM, 2003.

- 5 Wright designed a number of projects during his stay in Japan, including the campus for Jiyu Gakuen school in 1921.

- 6 Karel Teige, “Ten Years of Bauhaus,”, in Karel Teige, Modern Architecture in Czechoslovakia and Other Writings, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles 2000), p. 317.

- 7 László Moholy-Nagy and Willy Rötzler (eds.), Johannes Itten, Werke und Schriften, The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 116, No. 852, 1974, pp. 166–169.

- 8 Helmut Von Erffa, “The Bauhaus before 1922,” College Art Journal, Vol. 3, No. 1, Nov. 1943, pp. 14–20, here: p. 16.

- 9 Kenneth Frampton, Modern Architecture. A Critical History, Thames and Hudson, New York and London 1992, p. 123.

- 10 Johannes Itten, Mein Vorkurs am Bauhaus, O. Maier, Ravensburg 1963, p. 10.

- 11 Ibid.

- 12 Claudia Delank, Das imaginäre Japan in der Kunst. ‘Japanbilder’ vom Jugenstil bis zum Bauhaus, iudicium, Munich 1996, p. 152.

- 13 Henry P. Raleigh, “Johannes Itten and the Background of Modern Art Education,” Art Journal, Vol. 27, No.3, 1968, pp. 284–287, p. 302.

- 14 Iwao Yamawaki, “Reminiscences of Dessau,” in: Design Issues, Vol. 2, No. 2, Autumn, 1985, p. 56.

- 15 Ibid.

- 16 Michiko Yamawaki, Bauhausu to chanoyu, edited by Kawahata Naomichi, Shinchōsha Tokyo 1995, pp. 10–11.

- 17 Ibid., pp. 39–40.

- 18 Ibid.

- 19 Yamawaki, Bauhausu to chanoyu, p.45.

- 20 Yamawaki, “Reminiscences of Dessau,” p. 57.

- 21 It is surprising none of these books, which provide important first-hand accounts of the Bauhaus experience, have been translated.

- 22 The details of Shounan Mizukoshi’s Nanga lecture at the Itten-Schule, was revealed by Yoshimasa Kaneko’s following article. Yoshimasa Kaneko, "A Study on the Educational Relationship between Johannes Itten and some Japanese People. -With a Special Reference to the Activities of Shounan Mizukoshi and Kuniyoshi Obara," Daigaku-Bijutsukyoiku-Gakkaishi, No.32, 2000, 133-140. Concerning Shounan Mizukoshi, Yoshimasa Kaneko wrote also in his following English articles. Yoshimasa Kaneko, "Johannes Itten’s Design Education and Japan," in: Journal of the Asian Design International Conference, Vol.1, (6th ADC in Tsukuba, Japan), published in CD-ROM, 2003, (in English), np. Yoshimasa Kaneko, <Relationship between Johannes Itten and some Japanese in Berlin>, Bulletin of JSSD (Japanese Society for the Science of Design) Vol.50, No.6, 2004, pp.1–10 (in Japanese with English summary). Yoshimasa Kaneko, "Johannes Itten and Zen," in: Hrsg. von Christoph Wagner, Esoterik am Bauhaus. Eine Revision der Moderne?, Regensburger Studien zur Kunstgeschichte 1, Verlag Schnell&Steiner GmbH, 2009, pp.150-172 (in English).

- 23 Nagai, the son of a notable Japanese organic chemist and pharmacologist and his German wife (Therese née Schumacher, who served as professor of German language at the Japan Women’s University), was both bilingual and bicultural. Perhaps because of this personal history, he became known as an effective facilitator of transnational cultural dialogue, as well as a key formulator of Japan’s policy of tolerance towards the Jews, personally warding off German demands to change it. Nagai is remembered not only as a networker and supporter of the Japanese in interwar Germany, but also as a member of the group of Japanese diplomats that resisted intolerance toward Jews. His role in this resistance was analyzed in the book Japanese Diplomats and Jewish Refugees by Pamela Sakamoto. Also Kaneko wrote about Nagai and his activities in Yoshimasa Kaneko, "Johannes Itten’s Design Education and Japan," in: Journal of the Asian Design International Conference, Vol.1, (6th ADC in Tsukuba, Japan), published in CD-ROM, 2003, (in English), np.

- 24 Yoshimasa Kaneko clarified the relation between Johannes Itten and Obara Kuniyoshi, in the context of Mizukoshi Shōnan’s Nanga lecture at the Itten-Schule, in his article in 2000. And it was also written in his English articles. Kaneko, "A Study on the Educational Relationship," 2000, pp. 133–140; Kaneko, "Johannes Itten’s Design Education and Japan," 2003 (in English), n.p.; Kaneko, "Johannes Itten and Zen,", 2009, pp. 150–172 (in English).

- 25 Kaneko, "Johannes Itten’s Design Education and Japan," 2003 (in English), np.

- 26 Concerning these details of Itten-Schule’s morning practice, refer to the following articles. Yoshimasa Kaneko, "A Study on the accepting process of the formative education from Ittenschule to Japan. -Based on the achievements of Mrs. Mitsuko Yamamuro and Mrs. Kazuko Sasagawa," in: Bijutsukyoikugaku, No.16, 1995, pp.85–99. Kaneko, "Johannes Itten’s Design Education and Japan," 2003, (in English), n.p.

- 27 Concerning Yumeji Takehisa’s lecture at the Itten-Schule, Yoshimasa Kaneko carified in the following articles, based on the texts of Yumeji Takehisa, the works of Yumeji for the lecture, and the materials of Yumeji’s students. Kaneko, "A Study on the Lessons of 'Japanese Picture' at the Itten Schule," in: Daigaku-Bijutsukyoiku-Gakkaishi, 1993, pp.247–256. (in Japanese with English summary); Kaneko, "A Study on the Art Education of Yumeji Takehisa at the Ittenschule," in: Daigaku-Bijutsukyoiku-Gakkaishi, No. 33, 2001, pp.143–150. (in Japanese with English summary); Kaneko, "Johannes Itten’s Design Education and Japan," in: Journal of the Asian Design International Conference, Vol.1, (6th ADC in Tsukuba, Japan), published in CD-ROM, 2003, (in English), n.p.; Kaneko, "Johannes Itten and Zen," 2009, pp.150–172 (in English).

- 28 Richard S. Thornton, “Japanese Posters. The First 100 Years,” in: Design Issues, Vol. 6, No. 1, 1989, p. 11.

- 29 Yasuko Suga, “Japanese Craft Industry in the Period of Modernism as seen through Imai Kazuko and the Jiyū Gakuen Institute for Art and Craft Studies,” in: Bulletin of JSSA, Vol. 54, No. 2, 2007, pp. 9–18, here: p. 137.

- 30 Kaneko, "A Study on the accepting process of the formative education from Ittenschule to Japan," 1995, pp.85-99.

- 31 According to Czechoslovakian police documentation, Imai Kazuko (b. 30 June 1910 in Tokyo) lived on Praha II č.p. 1748 Václavská ul. 33 in Pension Žena from 25 August 1931 (her registration of residence voided in Berlin on 15 March 1932). Yamamuro Mitsuko (b. 18 March 1911 in Tokyo) lived at the same address and her paperwork was voided at the same place and time.

- 32 Kaneko, "A Study on the accepting process of the formative education from Ittenschule to Japan," 1995, pp.85-99; Kaneko, "Johannes Itten’s Design Education and Japan," 2003, (in English), n.p.

- 33 Kaneko, "A Study on the accepting process of the formative education from Ittenschule to Japan," 1995, pp.85-99; Kaneko, "Johannes Itten’s Design Education and Japan," 2003, (in English), n.p.; Yoshimasa Kaneko, "Jiyu-Gakuen students who studied at the Itten-Schule," in: Yasuaki Okamoto (Ed.), Johannes Itten Wege zur Kunst Ronbun-Shu (Academic articles collections), The special publication based on the conferences that were held during exhibition, Utsunomiya museum, 2005, pp.53–80(in Japanese).

- 34 Kaneko, "A Study on the accepting process of the formative education from Ittenschule to Japan," 1995, pp.85-99.

- 35 Yoshimasa Kaneko confirmed that Imai (Sasagawa) went to the Reimann-Schule after her lessons at the Itten-Schule, through his interviews with Imai (Sasagawa) in 1993.

- 36 Suga, “Japanese Craft Industry in the Period of Modernism,” p. 12.

- 37 Kaneko, "Johannes Itten’s Design Education and Japan," 2003, (in English), n.p.

- 38 Kaneko, "Johannes Itten’s Design Education and Japan," 2003, (in English).

- 39 The relation between Renshichiro Kawakita and Yamamuro &Imai (Sasagawa) was revealed by Yoshimasa Kaneko’s article in 1995. Concerning this relation, refer to the following articles. Kaneko, "A Study on the accepting process of the formative education from Ittenschule to Japan," 1995, pp.85-99; Kaneko, "Johannes Itten’s Design Education and Japan," 2003 (in English), n.p.