Meyer’s Russia, or the Land that Never Was

Communal hall from the ZAD Notre Dame des Landes, built in France circa 2017, courtesy Kristin Ross.

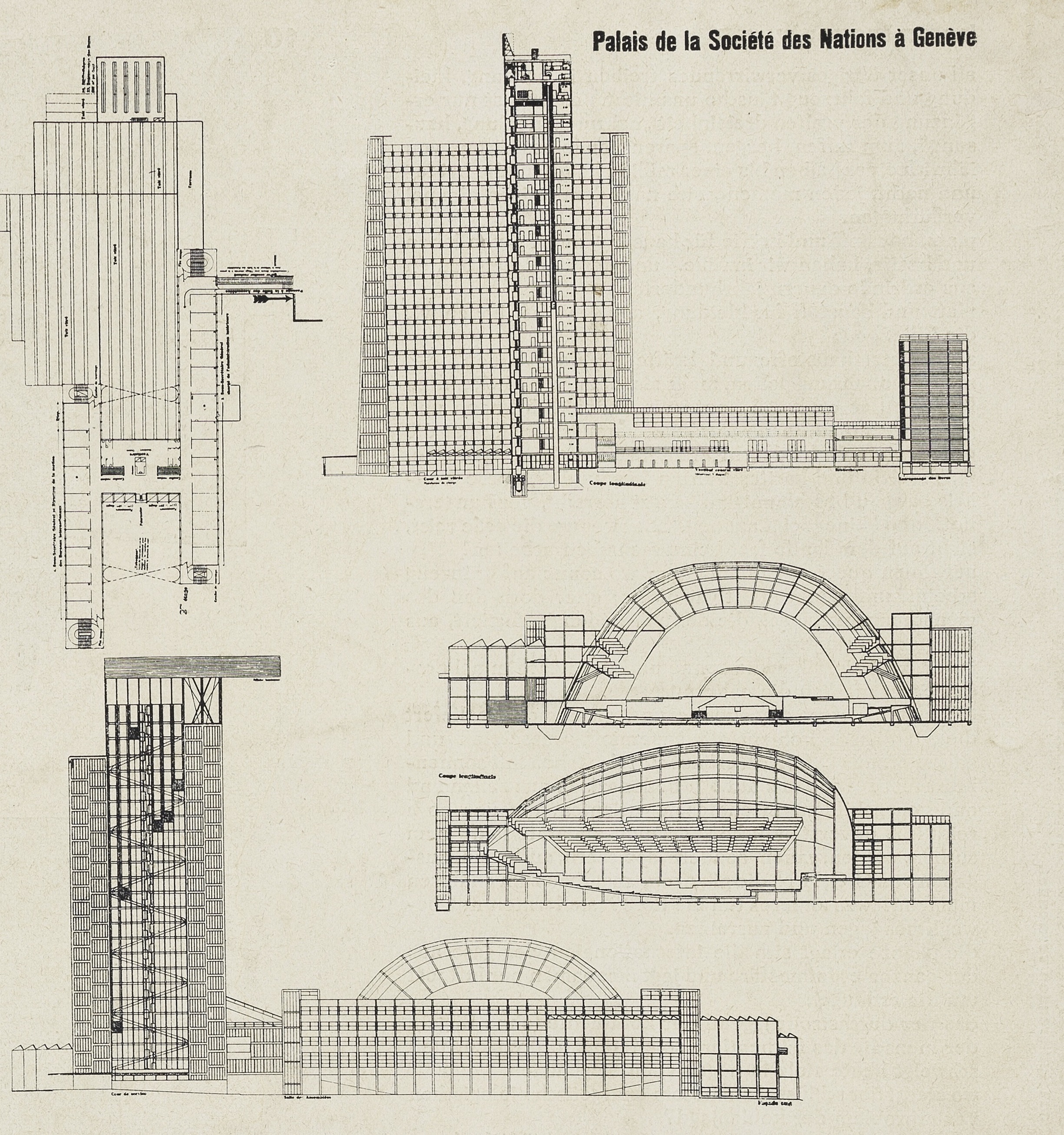

Original plans for the Palace of the League of Nations, Geneva: axonometry, draft: Hannes Meyer / Hans Wittwer, 1927. Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin. / © Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau (Meyer) / Sondra Wittwer (Wittwer).

It is quite hard to know where to start with Hannes Meyer in Moscow. It’s hard because, while there is plenty of documentation on him and his team in the Bauhaus Brigade—as well as other Western designers and architects (of these, Ernst May is at least as significant as Meyer, as is the Dutch designer Mart Stam, and each went on to produce more substantial work than Meyer after their respective Russian episodes)—the legacy of his work there presents certain difficulties in evaluating. Thus, some questions that arise when considering the presence of Western designers in the USSR are these: how can we measure significance?; what was the potential importance of the work and vision of such planners and architects in the structures and unfolding of the first and second five year plans that reorganized Russia on a scale of necessity beyond their real capacity to intervene?

In the end Meyer and the others dropped out, left their teams in chaos, accepted defeat. The report of a visit to Russia in 1936 (the year of Meyer’s departure) entitled Moscow in the Making, written by Sir Ernest and Lady Shena Simon—planners of the suburb of Wythenshawe in Manchester—together with academics W.A. Robson and J. Jewkes, contains no reference to any of these men, nor other teams who had set up shop there. It is as if these British industrialists and economic specialists, typical of curious travelers from the West, encountered no trace of Meyer and the others, no visible impact of their work; and this at a moment when the fame of the Bauhaus in exile was spreading throughout the world.

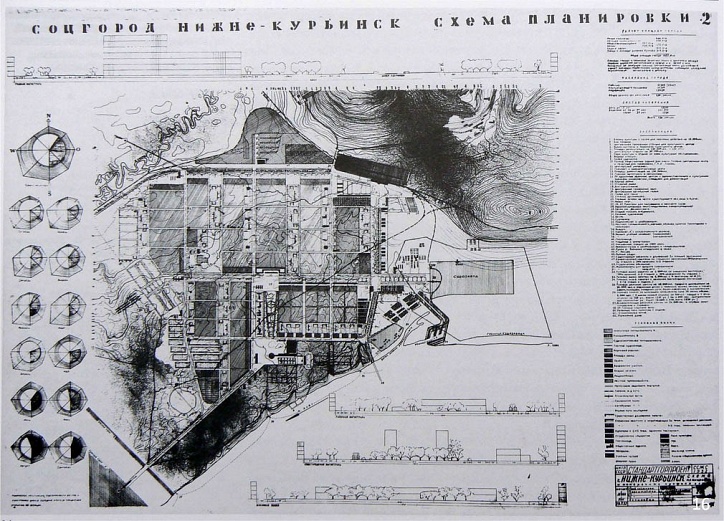

We know enough of Meyer to understand the logic of bracketing his work in Moscow between his previous projects in Germany and his later Mexican activities. Claude Schnaidt’s book Hannes Meyer, Bauten, Projekte und Schriften (1965) remains a good reference. but we can’t set out in our search by studying any one building, nor indeed a successful piece of city planning on the scale that he envisaged for Moscow, Nishni-Kurinsk, Sozgorod-Gorki or Birobidjan. We can speculate from, interrogate or interpret plans or other archival records, according to the well-worked relationship between modern(ist) architecture and design on the one hand, and socialist rationality on the other—that is, within a framework of architecture and design history—along with critical theory—as they have developed in the last three decades. We could draw up a dossier of Meyer’s pedagogical projects in Moscow and map his design methods and his thinking around architecture as a collective process. But once done, what might this show? That Meyer, the socialist director of the Bauhaus, was a missing link? To what end? Perhaps, in the final analysis, to nothing. Or to nothing other than the complexity of our own historical delusions and desires for a better outcome to the last century than the one we are currently living through?

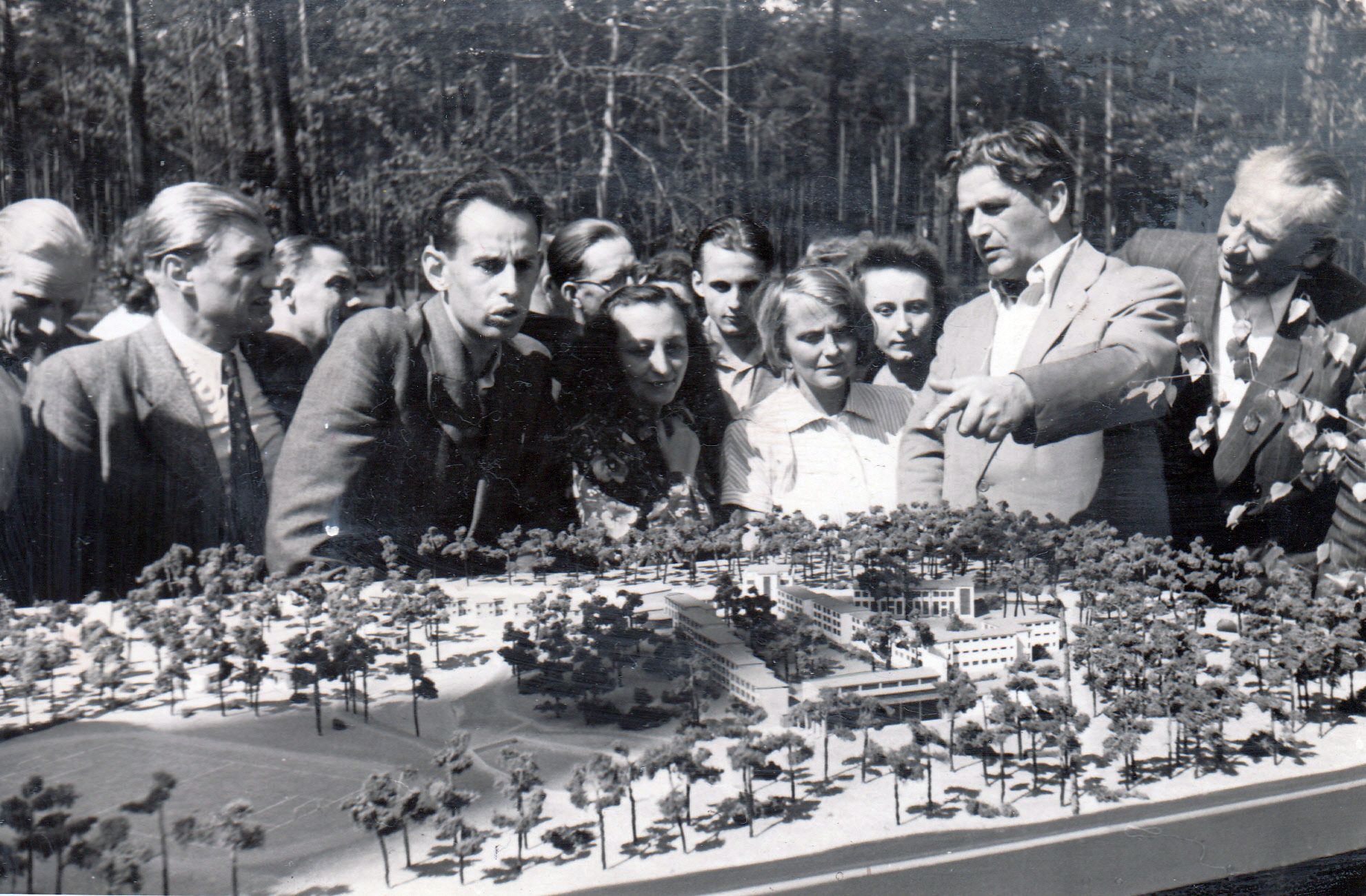

Hannes Meyer, Plan for Greater Moscow, unknown photographer, Bauhaus-Universität Weimar, Archiv der Moderne, © Heirs after Hannes Meyer.

Though each are brief, two recent books deal adequately with such matters: The co-op principle – Hannes Meyer and the Concept of Collective Design (from the Bauhaus Foundation, Dessau 2015) and Bauhaus – Hannes Meyer, Proyecto, conceptos y trayectoria by Bernardo Ynzenga (2017). Both books provide a good sense of how Meyer replaced the architect-as-master-storyteller with principles of cooperation, making the architect a participant in a process sensitive to collective political needs, as well as landscape, the movements of everyday life as much as the grandest of political perspectives. Employing a very different approach, K. Michael Hays in his Modernism and the Posthumanist Subject: The Architecture of Hannes Meyer and Ludwig Hilberseimer engages in a fascinating exploration of Meyer’s thinking within the historico-critical framework of Benjamin and Adorno’s thoughts on the commodity. For example, Hays writes: “Meyer’s shift at the Bauhaus amounts to the abandonment of the notion of the resistant avant-garde artist in favor of some other role that we might call, following Benjamin’s model, ‘the artist as producer’….”1 This theme indeed resituates Meyer’s work within twentieth century utopian, critical reflection, but has little if any bearing on his life and work in Moscow. In any case, Meyer himself is resistant to such thinking: to the end of his life he remained an uncritical admirer of Stalin(ism), just like the many fellow travelers and visitors to the USSR, of whom (let us admit it) he was just one … the one who happened to have been a director of the Bauhaus.

On his excellent website and blog, The Charnel House, Ross Laurence Wolfe has posted an essay of Meyer’s demonstrating this fidelity to the USSR, something I believe to be perfectly understandable within the range of political positions extant amid the general wartime situation of 1942. Wolfe explains:

“Yesterday I discovered a rare article Meyer wrote in 1942, originally in Spanish, on the architectural profession in the Soviet Union. It was translated into English and published by Harvard’s student design magazine TASK in 1943. The article is interesting in several respects. First, because it displays no bitterness whatsoever [with] the Stalinist regime that forced Meyer into exile … [along with] many of his friends. Second, because the pioneering modernist implicitly repudiates many of his earlier positions on the role of architecture in modern society, criticizing the avant-garde architects at VKhUTEMAS, and providing a ‘dialectical’ justification for proto-postmodernist eclecticism. Third, because it includes a number of facts and figures, which are interesting even though they are without a doubt inaccurate or misleading.”

But in this political complexity and ambivalence, one perspective and another call each other into question.

Where to go with Meyer, then, for us now? From these politics and urbanisms and architectures of our time, which is the time of the Bauhaus’s own centenary? A fascinating article from 2013 by Hideo Tomita and Masato Ishii, “The Influence of Hannes Meyer and the Bauhaus Brigade on 1930s Soviet Architecture,” sets out to explore the “psychological effects” they see Meyer as having understood to be crucial for urban planning and design. Their exploration of his Moscow plans unfold a vision of center and satellites, power and movement and ceremonial public space structured to facilitate mass demonstrations. But perhaps now, after so many discussions of the blurred borderlines and distinctions between different forms of authoritarian state formation—as in, for example, of Hannah Arendt’s foundational text—might we not suspect that Meyer, in some sense, should now be compared to the urban planning of Albert Speer and his Nazified cityscapes as depicted by Leni Riefenstahl?

It’s not a comfortable thought.

Hannes Meyer, Plan for the sotsgorod Nizhne-Kurinsk, 1932, © Heirs after Hannes Meyer.

Part Two

Now I want to start thinking from scratch about Hannes Meyer, the Bauhaus and Moscow, from here and from these images: one a communal hall from the ZAD Notre Dame des Landes, built in France circa 2017; the other Meyer’s design for the competition for the League of Nations building in 1927. The one is built by activists; the other is a piece of paper. Re-starting this way I am marking a difference between levels of cooperation, collectivity, struggle and efficacy in national, international and local situations across historical time and place. The Zone à Défendre (a play on the official phrase, zone/development) almost destroyed by the French government earlier this year was one outcome in an over half century-long struggle against the expropriation of agricultural land for a second airport at Nantes. In the end, it was a utopian exercise in cooperation and self-sufficiency in the face of capitalized agricultural production and the commodification of everything. Ultimately, the ZAD fulfilled its core objective—the airport was cancelled—but in the process it was nearly destroyed by the “forces of order.” Nevertheless, they have subsisted and developed in the face of that blow.

This movement has outlasted many a revolution. I begin from here as a way of asking what (on earth) was Meyer (actually) doing in Moscow, and in what ways, as we reflect back on the period of the first Five Year Plan, might he have been doing it for us now? How might we learn to periodize struggles without foreclosing on their future affectivity as well as their various singularities; the struggle to modernize Russia in the first decades of the Revolution, and the struggle to resist the “modernity” of huge capital investment in a new airport in our contemporary moment. The comparison is, in fact, telling. The Soviet model engaged in the massive expropriation of small property and farming by the state, while resistance to the second Nantes airport in France succeeded in arresting the same process of expropriation, albeit the latter was for purely capitalist ends. How, then, can we think of the rational and cooperative ideals of Meyer’s town planning and building design in the period when what Kristin Ross has named “luxe communal” (communal luxury) emerged out of the extended after-effects of the Paris Commune and William Morris’s theories, as a riposte to the concreting over of everything in the name of progress.

Communal hall from the ZAD Notre Dame des Landes, built in France circa 2017, courtesy Kristin Ross.

To come at this narrative from a slightly different direction: while Meyer and his brigade walked in at the end of electrification-plus-the-Soviet, intent on building upon what it had or had not yet built, the anonymous collective that fashioned the ZAD (most of its members took the same first name) could ironically be called a soviet of a new kind (genus Occupy); without electricity and with-out—problematically it is true—the state. Building a huge inside, a nation state of socialism, and hacking together a small outside within the capitalist nation state are not quite the same thing. On the eve of this centenary, the differences between them right now might excite our curiosity about the ideals of the Bauhaus at its most left-leaning edges. After all, Meyer was neither Walter Gropius nor Mies van der Rohe. That’s how we honor him—for never having built a bunny club or a cityscape of tower blocks, however formally exquisite these might still be. We honor him for having gone from Moscow to Mexico rather than from continental Europe to Chicago or London. But maybe what Meyer and the ZAD share is that both of them are ideas or ideals of freedom-in-cooperation, even though the latter might, inevitably, find itself subsumed, despite itself, under the neo-liberal economy of world agriculture. The ZAD was neither Thoreau’s Walden nor William Morris’ News from Nowhere, but just a flash in the here and now.

What I am trying to do, then, is to think of Meyer as a drop in the ocean, not as an outstanding event in the history of living architecture. Someone we might slip in alongside Paolo Soleri or Herman Muthesius; or position next to the early Archigram’s critique of dwelling, or Martin Pawley’s Architecture v Housing, or the problem of colonialism and imperialism and post-colonial design, or even such a classic conundrum as the gap between Alison and Peter Smithsons’ social housing in east London and their Economist Plaza on St James Street. Feminist and queer rethinking of space and building: whatever, just resituate! A fragment, no more than that. A moment in histories of critical theory and critical practices of building, architecture and design.

The photographs Meyer and his team made for the building of the so-called Jewish Autonomous region of Birobidjan show the old town. They picture what is to be flattened and replaced were their project, or any other, to have been implemented.

Uncannily it looks rather like what the ZAD had set out to save.

Meyer once wrote, oddly, but we can see how he is trying to clear the field:

“And personality? The heart?? The soul??? Our plea is for absolute segregation. Let the three be relegated to their own peculiar fields: the love urge, the enjoyment of nature, and social relations.”

Maybe the centenary is a chance to think how we might re-imagine their coexistence, as if from scratch.

Books and Articles Consulted

- Charles Bettelheim: Class Struggles in the USSR. Second Period: 1923–1930, http://www.marx2mao.com/PDFs/CSii77.pdf (10 September 2018).

- Mike Cooley: Architect or Bee: The Human Price of Technology, with a new introduction by Frances O’Grady, South End Press, Nottingham 2016 (1980)

- Boris Groys: The Total Art of Stalinism, Princeton University Press, London 2011.

- K Michael Hays: Modernism and the Posthumanist Subject. The Architecture of Hannes Meyer and Ludwig Hilberseimer, MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass. 1995.

- Mauvaise Troupe Collective: The Zad and NoTAV: Territorial Struggles and the Making of a New Political Intelligence, Verso, London 2018.

- Werner Möller & Raquel Franklin: the co-op principle. Hannes Meyer and the Concept of Collective Design, spector books, Leipzig 2015.

- Martin Pawley: Architecture versus Housing. A modern Dilemma, from the series: New concepts of architecture, Littlehampton Book Services Ltd, London 1971.

- Kristin Ross: Communal Luxury: The Political Imaginary of the Paris Commune, Verso, London 2016.

- Claude Schnaidt: Hannes Meyer, Bauten, Projekte und Schriften, A. Niggli, Teufen AR/Switzerland 1965.

- SOCIÉTÉ DES NATIONS: Concours d’architecture por l’édification d’un Palais de la Societé des Nations, a Genève, Switzerland 1927, https://biblio-archive.unog.ch/Dateien/CouncilMSD/C-239-M-97-1927_FR.pdf (10 September 2018).

- The Charnel House, https://thecharnelhouse.org/2015/09/10/hannes-meyer-the-new-world-die-neue-welt-1926/ (10 September 2018).

- Hideo Tomita & Masato Ishii: “The Influence of Hannes Meyer and the Bauhaus Brigade on 1930s Soviet Architecture,” in: JAABE, Vol.13, No.1, January 2014.

- Writings of Stalin and others on the Five-Year Plans online in www.marxists.org (10 September 2018).

- Bernardo Ynzenga: Bauhaus, Hannes Meyer, Proyecto, conceptos y trayectoria, Diseño Editorial, Spain 2017.

- 1 K. Michael Hays in his Modernism and the Posthumanist Subject: The Architecture of Hannes Meyer and Ludwig Hilberseimer, MIT Press, London 1992, p. 144.

.jpg?w=245&h=163&c=1)

.jpg?w=245&h=163&c=1)