“Walter Benjamin, compared ‘memory . . . the medium of past experience . . .’ to ‘the ground (which) is the medium in which dead cities lie interred.’”1

Working From Where We Are

Anni Albers’ and Alex Reed’s Jewelry Collection

Gold necklace from Tomb 7, Monte Albán, Oaxaca, Mexico, Display at Museo de las Culturas de Oaxaca, 1939.

Photo: Josef Albers, Courtesy of The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation.

Jade necklace from Tomb 7, Monte Albán, Oaxaca, Mexico, Display at Museo de las Culturas de Oaxaca, 1939. Photo: Josef Albers, Courtesy of The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation.

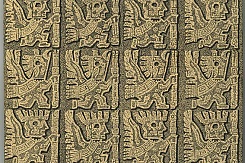

Not by nature acquisitive and certainly not art collectors, Josef and Anni Albers began in 1936 to collect Mexican figurines and other artifacts unearthed from that land’s memory. They described the country, which they first visited in 1935, as “the promised land of abstract art.”2 By collecting these buried remains of an ancient abstract art they transported the past into their own present. Their encounter with the ancient Zapotec jewelry discovered in Tomb 7 of the Monte Albán complex was a defining moment in what became a lifelong obsession. Now renowned as an example of Zapotec architecture, in the 1930s this archaeological site on the outskirts of Oaxaca was still being excavated.

Made using gold, silver, rock crystal, stones, shells and simple beads arranged in striking juxtapositions, the artifacts recovered from Tomb 7 were on display in the local museum (now the Museo de las Culturas de Oaxaca) when Josef Albers photographed them in July 1939. The Alberses were traveling with their friend and student Alexander “Bill” Reed. Anni’s parents had arrived in Veracruz as refugees from Nazi Germany just a few weeks before. They were among the fortunate ones who had managed, with significant difficulty and hardship, to escape Germany barely three months before the war began. Now they were safe in Mexico, where Josef and Anni Albers had found a contemplative space that nourished their art.

Returning to Black Mountain College that August, and inspired by the Monte Albán “trésor,” (as Anni’s named it) Albers and Reed began experimenting with everyday articles to create a strange and beautiful collection of objects of personal adornment. Their jewelry refused precious materials, relying instead on objects of utility—paperclips, bottle tops, hair pins, pencil erasers, cotton reels and washers—disassociated from their useful duties to create evocative forms and contrasts. Albers and Reed came to understand jewelry not as ornaments made valuable by the presence of rare gems and precious metals but by what the makers infused them with. They estimated the process of making, its “surprise and inventiveness,” bestowed their jewelry with a spiritual rather than material value, giving it meaning and clearing the path for “a new way of seeing.” In May 1941, a selection of their jewelry pieces was exhibited at the Willard Gallery in New York City.

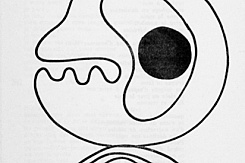

Anni Albers and Alexander Reed, Necklaces, ca. 1940

Bottle caps, beads, and metal chain (left), Pencil-top erasers, beads, and wire (right).

© The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2018.

In December 1941, the United States entered the Second World War. The previous year, as the US began to draft men into military service, the US Congress enacted laws allowing conscientious objectors to apply for alternative service. Bill Reed, a Quaker, registered as a conscientious objector and by 1941 had left BMC for a Quaker work camp in Pennsylvania. Anni Albers giving a talk at Black Mountain College in May 1942 was asked to refer in some way to defense work—work that, as Albers put it, “in the minds of so many of us [is] the most urgent work of the moment.” Most likely with Reed in mind, she chose to talk about their work together:

“Though our work has nothing to do with defense work, there was something right in asking [us] to connect it with it … [since] for many of us our work cannot be that of going into a munitions factory or of helping those who suffer in this war in a direct way. … To give our actions the meaning we want them to have implies questioning them anew … we felt our experiments perhaps could help to point out the merely transient value we attach to things … we tried to show that spiritual values are truly dominant … our work suggested that jewels no longer were the reserved privilege of the few, but property of everyone who cared to look about and was open to the beauty of the simple things around us.”

Anni Albers and Alexander Reed, Necklaces, ca. 1940

Spring, plastic rings, and metal tubing (left), Thread spools, bottle caps, beads, metal rings and chain, and ribbon (right).

© The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2018.

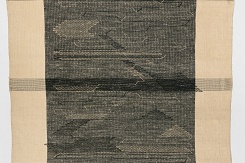

It was characteristic of Anni Albers to take the long and contemplative view. The Bauhaus, which she joined soon after the First World War, was in 1922 a refuge from a world beset by a “confusion of upset beliefs.”3 After 1933, as she and Josef discovered a new haven in Mexico, her deep empathy with the long buried and often forgotten ancient cultures of the Americas was always present in her daily thinking, informing her responses to the world. From this other “old” world she drew the courage and insight that, facing a new catastrophic world event, allowed her to affirm to her audience of May 1942 that:

“If we can more and more free ourselves from values other than spiritual, I believe we are going in the right direction. Every general movement is carried by small parts, by single people forming their way of believing and subordinating everything to this belief. We have to work from where we are. But just as you can go everywhere from any given point, so too the idea of any work, however small, can flow into an idea of true momentum.”4

- 1 Peter Demetz: “Introduction,” in: Walter Benjamin: Reflections: Essays, Aphorisms, Autobiographical Writings, trans. Edmund Jephcott, Peter Demetz (ed.). Schocken Books, New York 1986, p. 26.

- 2 Josef Albers in a joint letter from Josef and Anni Albers to Wassily and Nina Kandinsky, August 22, 1936, in Nicholas Fox Weber & Jessica Boissel: Josef Albers and Wassily Kandinsky. Friends in Exile. A Decade of Correspondence, 1929–1940, VT: Hudson Hills Press, Manchester 2010. Original French ed., Kandinsky-Albers: Une correspondance des années trente. Cahiers du Musée national d'art modern, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris 1998, Rev. ed., Yale University Press, New Haven and London 2015, p. 89. Josef Albers in a joint letter from Josef and Anni Albers to Wassily and Nina Kandinsky, August 22, 1936, in Nicholas Fox Weber & Jessica Boissel: Josef Albers and Wassily Kandinsky. Friends in Exile. A Decade of Correspondence, 1929–1940, VT: Hudson Hills Press, Manchester 2010. Original French ed., Kandinsky-Albers: Une correspondance des années trente. Cahiers du Musée national d'art modern, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris 1998, Rev. ed., Yale University Press, New Haven and London 2015, p. 89.

- 3 Anni Albers: “Weaving at the Bauhaus,” in: Brenda Danilowitz (ed.): Anni Albers: Selected Writings on Design, Wesleyan University Press, Middletown 2000, pp. 3–5.

- 4 All other quotations are from Anni Albers: “On Jewelry” a talk given at Black Mountain College, May 1942, Typescript in the archives of the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, Published in: Anni Albers: Selected Writings on Design. Wesleyan University Press, Middletown 2000, pp. 22–24; also accessible at: https://albersfoundation.org/teaching/anni-albers/lectures/.

_crop.jpg?w=245&h=163&c=1)

Kopie.jpg?w=245&h=163&c=1)