The publication Times of Rudeness: Design at an Impasse,1 organized by Lina Bo Bardi in the 1980s, was ultimately abandoned by her with the argument that it had no use, since “all would fall into a void.”2 Eventually it was published in 1994 by Isa Grinspum Ferraz and Marcelo Suzuki, then the co-chief editors and directors of the Instituto Bardi. The book was part of a series entitled Issues on Brazil,3 a set of titles that aimed to uncover important cultural matters that had influenced the sociocultural tissue of Brazil but had been neglected by other institutions and authors at the time.

The book included a collection of twelve texts and a couple of poems, all written as individual articles by Bo Bardi or by her colleagues: Bruno Zevi,4 a close friend of Bo Bardi’s who had been in contact with her since her days as an architecture magazine editor in Italy; Celso Furtado, a renowned economist who collaborated with Bo Bardi between 1958 and 1964 on proposals for Brazilian development, especially around issues of industrialization and culture as well as questions related to craftsmanship, the formation of labor and the teaching of a type of industrial design pedagogy linked to the cultural base of the country5; Glauber Rocha, the actor, director and key figure of Cinema Novo who was also a Bahia native with whom Bo Bardi was related as a fellow-member of the Tropicalistas movement; Flávio Motta, the artist, art historian and founder of Escola Livre de Artes Plásticas, and a number of other authors.

Each of the contributors argued in different ways for an understanding of Bahia and the Northeast Region of Brazil as the site where a popular basis for national values might be indentified—not in a folkloric or nationalistic way—but as a space where, disregarding form and techniques, there was an “underlying structure of possibilities.”

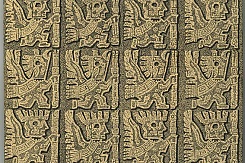

Images accompanied the different texts, deployed in such a way, as Bo Bardi explained, “quilts are quilts, ex-votos are presented as necessary objects and not as sculptures, cloths with appliqués are cloths with appliqués …” There is no re-interpretation of these objects but a mere desire to catalogue them as examples of “sporadic production of craftsmanship”—a theme with which the publication dealt with in depth.

Bo Bardi’s title suggests a negative or frustrated view of Design (with a capital D) as a regenerative societal force, as promised by the various modernist movements. In the late 1940s and early 1950s she had designed furniture with the Milanese rationalist architect Giancarlo Palanti (who emigrated to Brazil in 1946) at Studio Palma, where the two created modernist furniture in series, but later stopped working in industrial design projects, since “the abstract geometric forms of design and architecture had lost their transformative meaning and had become mere consuming and disposable products.”6

Bo Bardi continued to design furniture and other objects for her own projects, but the views she stated in this emblematic publication are key to understanding her view of architecture and design as a political act.

Having this text published on the online journal of Bauhaus Imaginista, reiterates Bo Bardi’s continuing relevance to the contemporary international discourse of design. It is with great enthusiasm that we share it for such a special occasion.

Sol Camacho

Cultural Director Instituto Bardi / Casa de Vidro

_crop.jpg?w=245&h=163&c=1)

Kopie.jpg?w=245&h=163&c=1)