Let us focus on Püschel’s own visual records for a moment: The collection of photographs of Püschel’s trip to North Korea in the 1950s includes a photograph of a young chemical worker in a laboratory.22 She has a writing pad in front of her which is open and upon which she might be documenting laboratory results. In her hands she holds a thermometer, while in front of her stands a shelf with numerous gas bottles, beakers and glass flasks. She is wearing a white protective coat. The room is flooded with daylight, which enters the laboratory through a large window, flowing through the shelf with the laboratory equipment and illuminating the right half of the chemical worker’s face. The chemical worker is almost imperceptibly smiling, provoking a gesture of a laughing look. Her eyes look to the left, as if she wants to look beyond the photographer, who cannot keep her from her work. Thus, her gaze leads her into the room, exceeding the encounter with the East German architect and photographer Püschel. Does she seek the gaze of a colleague in the room? Is she thinking of family members who survived one of the devastating battles in the first hot war of the global Cold War? … it’s a moment of work, waiting, research and gaze that might easily have found its place in Marker’s Coréennes: a moment with which Püschel makes an impression of North Korea for himself. That is, of the province Hamgyŏng-namdo and the people living there after the war, about which the GDR party newspaper Neues Deutschland was then reporting daily.

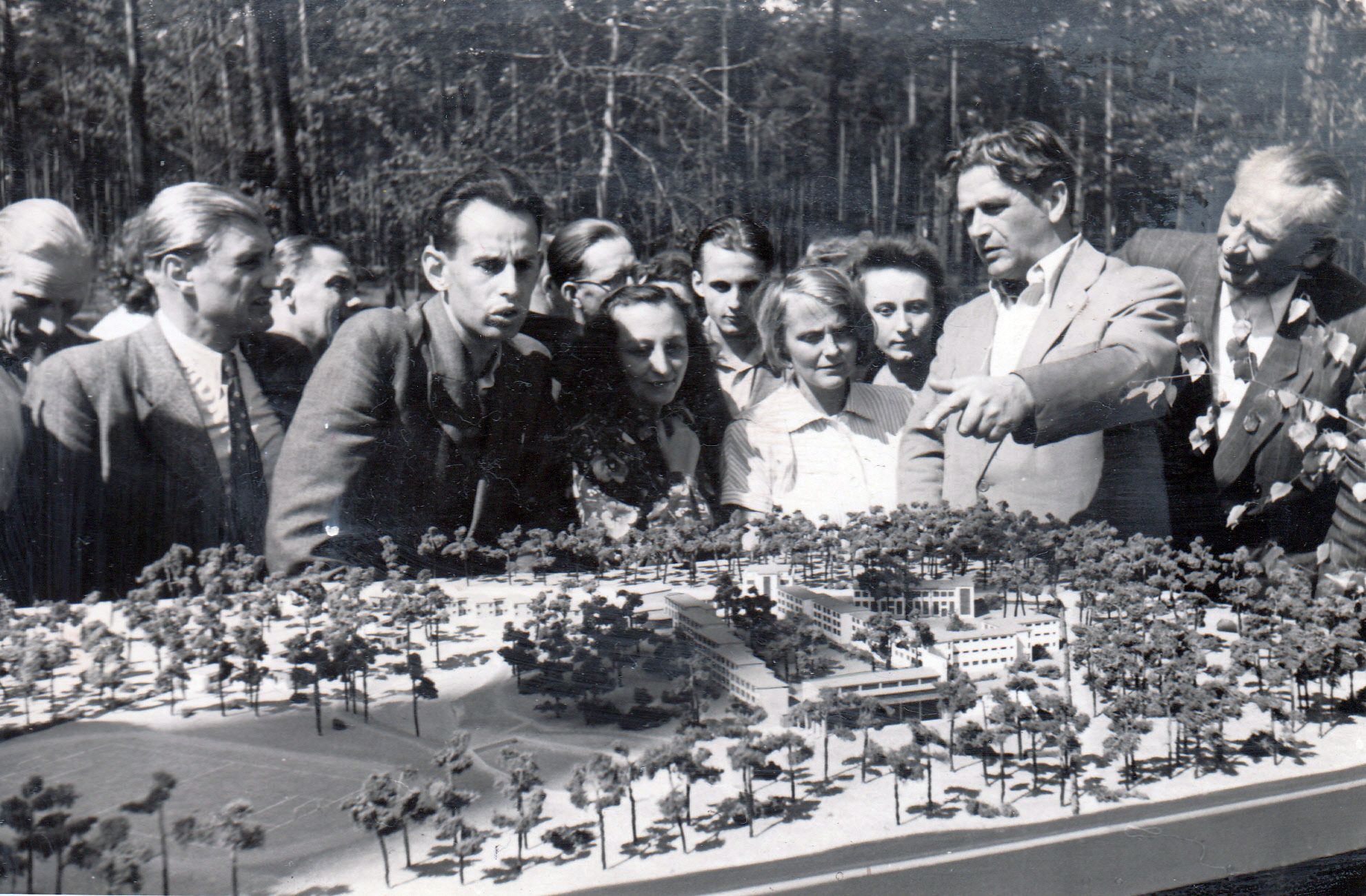

Püschel took plenty of photographs during his stay. He not only visited the provincial capital Hamhŭng, he also documented four forms of settlement construction in Hamgyŏng-namdo province, taken with a view to examining the power relations between different social orders. For example, he comments on the influence of Japanese colonization in Korea, which produced industrial buildings along the coastal areas, writing: “Here it is no longer the design that speaks, but only technology and economy.”23 This is also where a city planner speaks, who learned and rehearsed architecture as a design practice with Hannes Meyer and Ludwig Hilbesheimer at the Bauhaus in Dessau. Furthermore, Püschel’s photo albums contain photographic observations focusing on the natural landscapes of Hamgyŏng-namdo; as he writes in “Ein Überblick über die Entwicklung und Gestaltung koreanischer Siedlungsanlagen,” he visited the tomb of the parents of the founding king, Ri Song-Gä of the Choson dynasty, located near Hamhŭng; it also contains reproduced drawings of log houses belonging to the fire field farmers of the Kaima highlands, and a hand-drawn floor plan of Hamhŭng from 1956, etc.

In the photo album the landscape pictures are often combined as diptychs or triptychs. A factory installation—it could also be a collective farm—is photographed in color. All the other photographs are reproduced in black-and-white 35mm format. It is as if photographic observation provided a research tool to learn about a North Korean building history so as to understand both the historical structures left undestroyed by the Korea-Indochina war; as if the visual research of the region delivered a profound method for planning Hamhŭng’s postwar future, for the reconstruction of the city by the construction working group from the GDR is not only a project of “brotherly friendship,” undertaken in the context of the GDR’s internationalist reconstruction aid to North Korea, but also a comprehensive urban planning program (a residential city machine would be worth mentioning) for constituting a new socialist society after a war that had destroyed infrastructure and urban space and forced millions of people to flee. In other words, just as the founding of the GDR was a consequence of the Second World War, the establishment of the DPRK was also preceded by a war with a global dimension, who’s ceasefire was negotiated for months at the 1954 Geneva Conference of the United Nations.24 It seems as if it is the power of war, a power able to establish the modernist tabula rasa, is also considered the modernist principle of a Plan Voisin (translated literally as “neighborhood plan,” this was the name of Corbusier’s planned redevelopment of central Paris).

In North Korea, it was war itself that realized the utopian idea of a tabula rasa, enabling the building of a new city from scratch. The Second World War being only recently concluded, the partitioning of Korea after 1953 can be viewed as a symptom of the reorganization of a global social system orchestrated by competing powers, just like the formation of Europe’s so-called Iron Curtain, of which the Berlin Wall was a part. Notes Marker: “it’s naive to ask where the war comes from: the border is the war.”25 The Second World War was over, a Third World War had immediately begun: the Cold War. The Korean War was the first hot war of this global Cold War—begun only five years after the Second World War had ended. It is the devastating destructive power of these wars that creates the condition for constructing, spatializing, locating, delimiting, and programming a new—here socialist—society. The architect and Hamhŭng project interpreter Dong-Sam Sin writes: “As facilities to be planned for the functioning of life in the district, there are: district administration, cultural center with cinema, post office, police, bank, hotel, restaurants, department stores, polyclinic, pharmacies, craftsmen’s yard, central building yard, coal and other storage places, operation of street cleaning and garbage collection, fire brigade and finally, for the 11 or 12 residential complexes still schools, children’s facilities, shops and health facilities will be necessary. This will provide a crucial basis for the district’s planning and the second stage of the work in Hamhŭng can really get underway.”26 Atop the tabula rasa created by war, the construction working group envisioned a residential city machine, producing a socialist-Korean society in the entanglement of administrative, economic, vegetative, medical, logistical, productive, social and cultural principles that led to discussing “Korea[as] an example of proletarian internationalism.”27

Armin Linke.jpg?w=96)

.jpg?w=245&h=163&c=1)

.jpg?w=245&h=163&c=1)