Given his political background, it should not be astonishing that Bauhaus students reported how under Meyer they participated in discussions on diverse topics, followed class meetings in all workshops, and that the relationship between teachers and students became more cooperative. In his final vision, Meyer strived for an autonomous school of pupils—an idea of micro-political liberation and institutional critique with origins in anti-authoritarian branches of reform pedagogy and the cooperative movement. This orientation was also reflected in the School’s expanded guest lecturer program. When Meyer introduced additional courses from other fields of knowledge—such as philosophy, sociology, and the natural sciences—expanding the range of the curriculum and making it more horizontal, the Bauhaus masters arose in protest again. Meyer had also started to collaborate with colleagues outside the Bauhaus: the Czech functionalist and poet Karl Teige was a frequent visitor (the weaver Otti Berger’s text, “Stoffe im Raum,” was published in RED, Teige cultural journal); Mart Stam received a teaching assignment; Austro-Marxists such as Otto Neurath were invited to lecture; as was Graf Dürkheim, who lectured on anthroposophy. The Bauhaus remained polyphonic under Meyer but also more collective, egalitarian, and polytechnical.

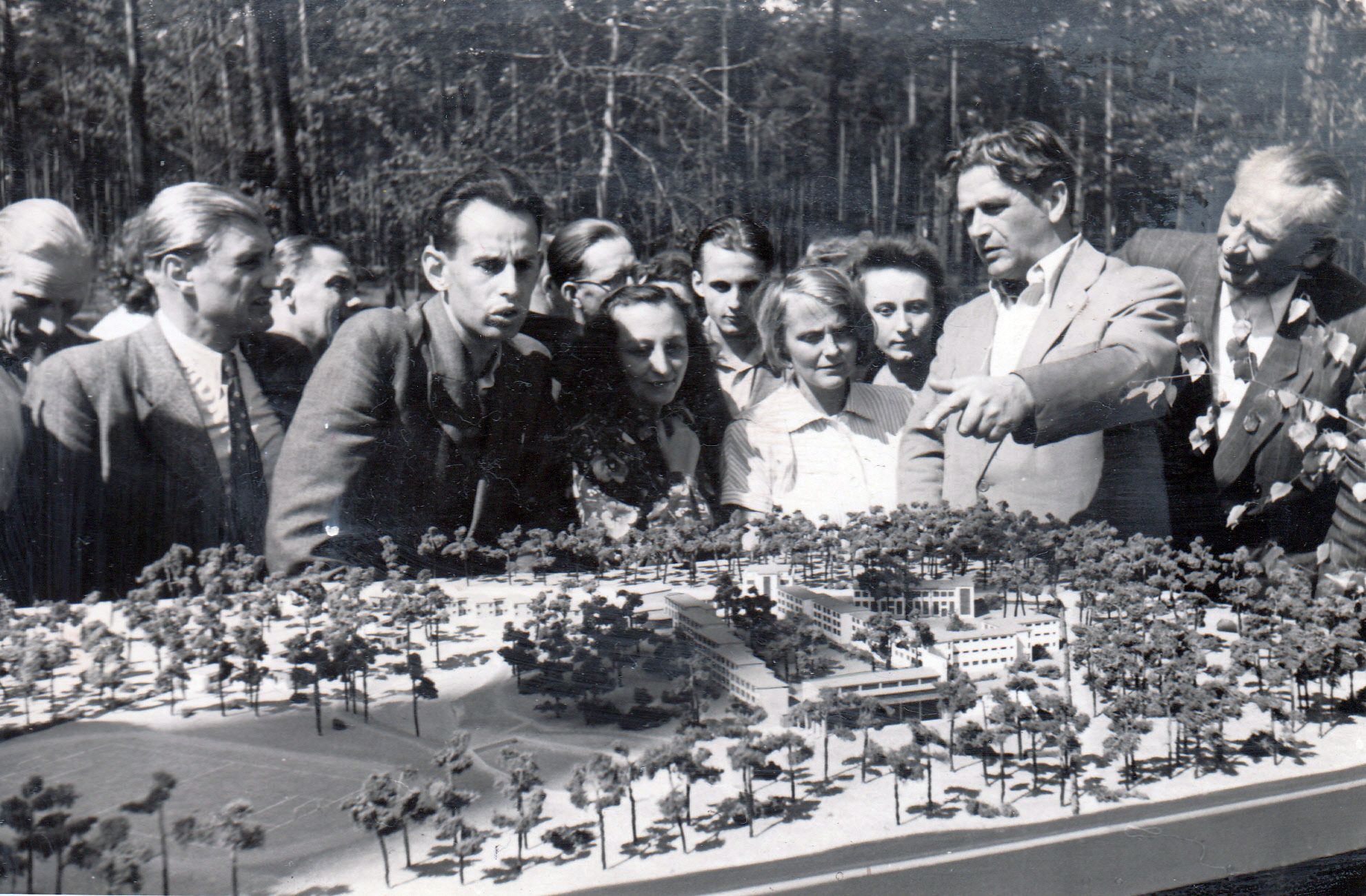

In the design and building process that went into the balcony houses in Dessau and the Federal Trade Union School in Bernau, students from various years worked together in so-called “vertical brigades.” All workshops were now open to women, who were also free to work at construction sites. Students were involved in researching the spatial, topographical, and social conditions of individual sites, and introduced to ideas then circulating internationally on the topic of urban planning and housing development. Investigating context and process was foregrounded, including considerations of climate factors in the landscape and the study of the usage and life patterns of prospective inhabitants. In this regard, dialogue between designer and users was promoted. The tasks of the design project and the knowledge required for it stood in the center of Bauhaus education.

… a new world

In his essay “The New World” from 1926, Meyer had already imagined a globalized world in which community and cooperation rather than technological innovation would shape the coming world order. “In Esperanto,” he claimed, “we construct a supranational language according to a law of least resistance, in standard shorthand a script with no tradition.”

Meyer, like Gropius, was a cosmopolitan. But Meyer’s vision of a designer sensitive to local conditions and usage also related to his socialist utopianism. His background in Basel might also have helped him in connecting diverse avant-garde ideas—socialist egalitarianism, anthroposophy, the Swiss coop movement—together with new insights derived from sociology, psychology, and the natural sciences. With his openness to diverse epistemic formations and disciplines, Meyer did not, as had Gropius, articulate his claims in a manifesto. Rather, his search concerned a new design subjectivity that would be able to adapt to emergent or unforeseen social contexts and material conditions. For Meyer, the designer of the future served the task, in opposition to the subjective notion of the vanguard artist, whose work grew out of an individual personality. In his imagination the Gestalter was a part of the world, of society, and the environment. This perspective including the larger physical/material context as well as the collective effort of different individuals collaborating together. Meyer also understood the environment where a building was situated—the landscape as he called it—was as important as the building site itself. This concept of landscape was also a rejoinder to nationalist and right-wing notions of “nation” and “homeland.” Political power structures might change, but the landscape, the material conditions constitutive of place, were vitally important considerations for designers—in contradistinction to that other trend of International Modernist architecture, which put its faith in a universalist methodology in denial of local conditions. Thus, it was not by chance that the University of Ile-Ife campus in Nigeria built by Arieh Sharon, one of Meyer’s most famous Bauhaus students as well as a collaborator on the Federal Trade Union School in Bernau, is an example of what today is called passive, climatic, culturally sensitive architecture.

In 1930, in a climate of rising right-wing nationalist ideological fervor, the Dessau-Anhalt authorities accused Meyer of “communist machinations,” dismissing him during the summer vacation. Internally, Kandinsky and other masters had already started to work on his dismissal. Coming only two years after his initial appointment, his firing may have been politically motivated, but it was not only due to right wing forces in the government. Meyer may have openly expressed solidarity with socialist and communist Bauhaus students but was not, like Moholy, a communist party member. Yet, his dismissal is still attributed to the strengthening of the Nazis in Dessau, while the role Bauhaus masters and associates possibly played remains unnoted. Meyer protested and wrote an open letter against the decision. His struggle was supported by communist newspapers, including the magazine of the student communist cell at the Bauhaus, published until 1932. With this, the scandal of a depoliticized Bauhaus began, and with it the story of a modernist migrant.

Having obtained an invitation from the Soviet government, Meyer moved to Moscow in the fall of 1930. Former Bauhaus students followed Meyer to the Soviet Union, working under the self-given name, “Bauhaus Brigade Red Front.” As with many other modernist architects of the time—Bruno Taut, Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky, and Mart Stam—Meyer and his former students worked on the large building initiative of the first five-year plan. Upon arrival in Moscow he gave lectures about the Bauhaus and started organizing a Bauhaus exhibition, shown the following summer in Moscow and in the winter of 1932 in Kharkiv, then capital of Ukraine. By then, however, he was already more occupied with questions arising from Soviet reality, working until 1936 for a number of design institutes, mostly in the field of urban planning. He also worked on the plans for various “socialist cities”—new towns that were strategically positioned all over the Soviet territory, including Birobidzhan, the capital of a newly-organized Jewish province near the Chinese Border. In addition, Meyer was also involved in theoretical work at the All-Union Academy of Architecture, where he headed the Department for Dwelling Architecture, Public Buildings, and Interior Design. Practice and conceptualization in this area were influenced by the ideas of the politician and theorist Nikolay Milyutin, who in 1930 had published the book Sotsgorod, bringing together the principles of the Neues Bauen with the specific conditions pertinent to the development of a new socialist way of life in the Soviet Union. In this regard, in 1934 Meyer began conducting independent research into the problems of constructing new Soviet housing, and the modernization and expansion of Moscow. This line of investigation was not unique: in the same year as Meyer was undertaking his research, Moisei Ginzburg, former leader of the Constructivist architects, published the book Dwelling, which summed up the findings of a five-year research project by the Section of Housing Typification of the Building Committee of the RSFSR. Meyer, however, believed that Ginzburg’s focus (affordable housing for all) was too obvious. He imagined that through the application of rhythms, proportions, and optical axes, living space could be truly integrated into the city. Plants also played a role in this project: a flower on a shelf, a tree in a courtyard, the green space of the Park of Culture and Leisure … according to Meyer these could all create an “ensemble.” This acknowledgment of the importance of the environment as an ensemble, or “landscape” was an important step towards a new building movement centered around the house as a product of design processes and crafts. For Meyer, the new Gestalter was sensitive to the many aspects of living. Even before the geopolitical changes of the 1930s and the period of war that followed, Meyer had become an advocate of ideas and pedagogical concepts not in accord with the socialist realism and rationality of the time. In Moscow and later in Mexico City, his ideas on life processes and environmental concerns, as well as his cooperative teaching method, led to opposition from colleagues as they had at the Bauhaus.

The circumstances under which Hannes Meyer left the USSR in 1936 are unclear. Possible reasons include financial troubles, personal conflicts, and the political challenges occasioned by the new socialist realism guidelines. But as we know today, his departure was not a function of any criticism he may have directed against Stalin’s regime. In 1937, after Meyer and his partner, the Bauhaus weaver Lena Bergner, had left for Switzerland, he joined the Swiss Communist Party; in Mexico the couple remained advocates of the Soviet cause, co-organizing publications and exhibitions.13 However, they left the USSR at the right moment. Many members of the émigré avant-garde, including several Bauhaus graduates, were unable to flee the Stalinist terror: many members of the Bauhaus brigade were imprisoned and killed by the system they had wanted to serve.14 Not so Meyer and Bergner. After a brief stay in the United States, the couple moved to Mexico in 1939, where in June Meyer accepted an invitation to become head of the newly formed Institute of Town and National Planning of Mexico. During his tenure he designed several unrealized projects, and was involved in writing, publishing, and editing books on social housing, urbanism, and anti-fascism.

Today, Meyer’s estate is housed in various collections and institutes: in the Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin, the archive of the Bauhaus Dessau Foundation, the German Museum of Architecture Frankfurt/Main (DAM), and the Institute for the History and Theory of Architecture at the ETH Zurich (gta). These collections possess unique indexing systems and disparate institutional and personal narratives. Not only have archival criteria and collection management systems in Swiss and German institutions been inherited from the time of the East-West split, the status of archival material on Bauhaus USSR survivors is generally incomplete and precarious. These two conditions informed research on Moving Away. Through varied archival holdings—photographs, letters, collages, pages from scrapbooks, diagrams, manifestos, architectural drawings, and town plans—an image of the relationship between teachers and students, the Bauhaus Dessau, the Soviet Union, and the communist and socialist ideals held by these individuals was partially unfolded. Working individually, a research group consisting of the art and architecture historians Tatiana Efrussi, Thomas Flierl, Daniel Talensik, Anja Guttenberger, and myself accessed the archives. Starting in 2017 we exchanged on our findings concerning Meyer’s Bauhaus tenure, the “Bauhaus Brigade,” and the gaps and contradictions we found in the institutional collections listed above.15

As a curatorial strategy and to open up new readings on documents about Meyer and his Bauhaus comrades, the contemporary artists Alice Creischer and Wendelien van Oldenborgh, along with theorists Adrian Rifkin and Doreen Mende were invited to produce “readings” of these institutionalized leftovers in order to understand the socialist background of the architects and their work and life (and death) in the Soviet Union.16 These commissions opened up new critical examinations of work contexts, migratory flights, and geopolitical conditions during the 1930s and 40s. They also cast light on contemporary habits of dealing with the past.17 Employing the expertise of visual artists in an exhibition dealing with historical documents, and with design and urban planning history in particular, allows for critical reflection on how we conceive history as well as the strategies used in re-narrating historical material, no matter how scattered and incomplete. Today, contemporary artists (and curators) employ diverse methods and different bodies of knowledge in their respective practices, reflecting on the medium of representation while also creating counter-narratives to the national frames within which knowledge is customarily produced. Such a contextual, trans-historical approach appears removed from notions the Bauhaus once championed concerning the figure of the artist-designer. However, this difference creates a subliminal history of cross-cultural practices that still communicate with each other across time and space. In any case, an answer to the question of what social role artistic practice should play and what elements would go into the new subjectivity of designers had changed between the time the School opened and when it closed. Yet, this search for answers remains of interest, as the question of the societal function of art and design remains unresolved; not a cross-disciplinary approach, which a hundred years after the Bauhaus began has become the norm, but the social function of the arts in general, which for the most part are restricted to a mode of representation ensconced within the security of institutional enframement. How to be involved in society as both an active member and a socially conscious artist/designer remains part of an imagined and unrealized Bauhaus. This question ultimately guided me to follow Lena Bergner and Hannes Meyer to Mexico City.

the proletarian artist

_Vorderseite.jpg?w=964)

_Vorderseite_2.jpg?w=964)

.jpg?w=245&h=163&c=1)

.jpg?w=245&h=163&c=1)