Nach der mexikanischen Revolution (1910–1924) prägte der langwierige Kampf um Demokratie, Fortschritt und soziale Gerechtigkeit die neue Politik des jungen mexikanischen Staates. Auf die hohe Analphabetenrate reagierte diese Politik jedoch zunächst verhalten. Noch um 1940 konnte etwa die Hälfte der erwachsenen Mexikaner weder lesen noch schreiben.1 Im Jahr 1944 waren von über fünf Millionen schulpflichtigen Kindern gerade einmal 2.765.000 zur Primarschule eingeschrieben; für alle anderen gab es keine Unterrichtsmöglichkeiten.2 Zur Förderung des Schulbaus richtete der damalige Präsident Manuel Ávila Camacho im Februar 1944 ein staatliches Schulbaukomitee ein und beschloss ein Schulbauprogramm, dessen erster Bericht drei Jahre später erscheinen sollte.3 In dem mehr als 420 Seiten umfassenden Report stechen Bergners Bildstatistiken zur Visualisierung der Schulsituation in den Bundesstaaten hervor. Sie lassen auf ihre Vertrautheit mit Neuraths bildpädagogischer Methodenarbeit schließen, mit der sie in ganz verschiedenen Situationen und geopolitischen Kontexten in Kontakt gekommen sein kann.

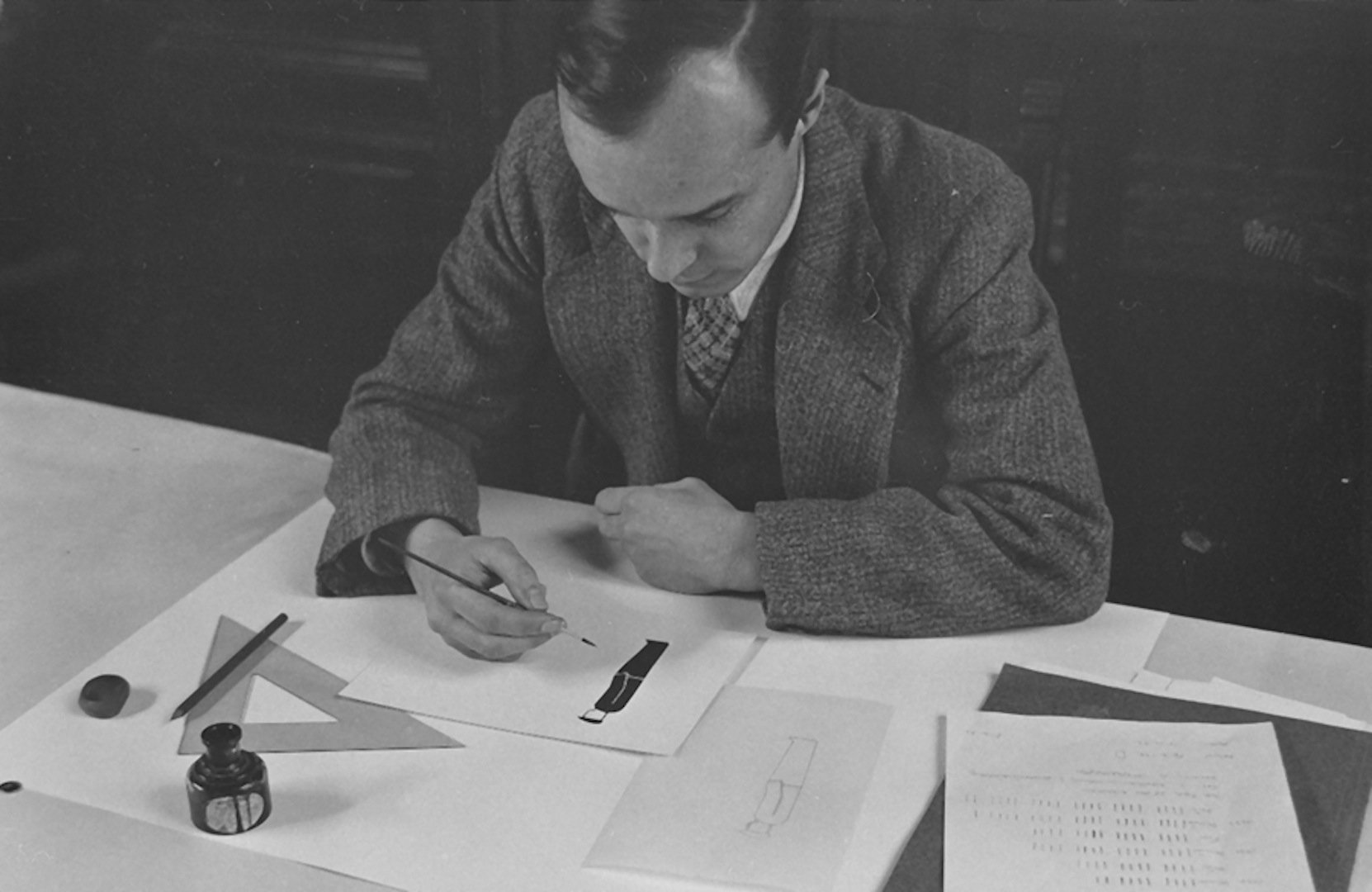

Am Bauhaus, wo Bergner von 1926 bis 1929 studierte, wurde sie nicht nur in der Webereiklasse ausgebildet. Eine Besonderheit ihres Studiums war dessen Ausweitung auf die Reklamewerkstatt und auf technische Fächer: Im ersten Studienjahr besuchte sie den Kurs „Schrift“ bei Joost Schmidt sowie den Unterricht zur Darstellenden Geometrie bei Friedrich Köhn (Dipl. Ing.) und im Fachzeichnen bei Karl Fieger (Architekt). Neben ihrer Ausbildung in neuen visuellen Darstellungstechniken und der Gebrauchsgrafik ist es zudem wahrscheinlich, dass Bergner bereits am Bauhaus ihre Bekanntschaft mit der „Wiener Methode der Bildstatistik“ (Isotype) machte. Dieses neuartige Bildsprachesystem zur Darstellung sozialer und ökonomischer Mechanismen geht auf Otto Neurath zurück.

Neurath leitete von 1924 bis 1934 das Gesellschafts- und Wirtschaftsmuseum in Wien. Der weite Umfang dieser Institution gab ihm die Möglichkeit, die „Wiener Methode der Bildstatistik“ in verschiedenen Auftragsarbeiten zu entwickeln. Zu seiner Unterstützung engagierte er ab 1925 Marie Reidemeister und ab 1929 Gerd Arntz als Chefgrafiker. Nachdem Neurath noch vor dem Ersten Weltkrieg auf einer Studienreise in die Balkanländer eine Analphabetenrate von 60 Prozent beobachtet hatte, war für ihn die Überwindung der Kluft zwischen Gebildeten und Ungebildeten zu einem Problem geworden, das er mit der Bildstatistik lösen wollte. Sein Ziel bestand in der Kreation von Piktogramm-ähnlichen Grafiken als Zähleinheiten für soziale Zusammenhänge, die auch Menschen mit mangelnder Lesekompetenz vermittelt werden konnten. Zudem wollte Neurath die Distanz zwischen Völkern und Sprachgruppen verringern – ein Ziel, das sich auf Versuche des Wiener Kreises stützte, standardisierte Ausdrücke zu formulieren, die kulturübergreifend funktionierten. Auf Einladung von Hannes Meyer, dem linksorientierten Nachfolger von Walter Gropius, referierte Neurath am 27. Mai 1929 am Bauhaus zu „Bildstatistik und Gegenwart“.4

Neurath war überzeugt, dass es auf Basis von technischen Innovationen möglich sei, die Lebensform zu ändern. Die Verpflichtung auf die Technik war aber kein spezifisch linksgerichtetes Phänomen.5 Bereits mit der Ausrichtung des Bauhauses auf die industrielle Produktion ab circa 1923, als Gropius ihre Einheit mit der Kunst postulierte, wurde die Technik als bestimmende Kraft der Zeit anerkannt. Meyer demontierte diese Einheit allerdings, um den Technik-Begriff um eine soziale Kompetenz im Sinne einer Methode zu erweitern. Mit diesem Begriffsverständnis war die Übereinstimmung mit Neurath eklatant: Beide teilten die Auffassung, dass der Gestalter eine technische soziale Funktion haben sollte. Neurath bezeichnete diesen Gestalter-Typus als Gesellschaftstechniker. Er sollte, wie der mechanische Techniker, auf die Umgestaltung der Welt durch wissenschaftliche Arbeit abzielen – und zwar durch die systematische Analyse moderner Statistik. Meyer formulierte diesen Gedanken analog: „bauen ist kein ästhetischer prozeß[…] das funktionelle diagramm und das ökonomische programm sind die ausschlaggebenden richtlinien des bauvorhabens.[…] bauen ist nur organisation: soziale, technische, ökonomische, psychische organisation.“6 Wie Meyer das „bauen“ betrachtete Neurath die Bildstatistik als Teil eines gesamtgesellschaftlichen Prozesses. Die Verwendung von universellen Kommunikationsformen würde helfen, diese Gesellschaft aufzubauen, wobei die Gemeinsamkeit zwischen Neurath und Meyer in der Forderung bestand, das Leben auf Grundlage moderner wissenschaftlicher Prinzipien zu reformieren, anstatt etwa auf anthroposophischen, nationalistischen, völkischen oder nazistischen Maximen. Es ist naheliegend, dass Bergner Neuraths Vorlesung zur Bildstatistik gehört hatte. Nach einem Praxissemester in der Färbereischule in Sorau im Winter 1928/1929 war sie seit April 1929 wieder am Bauhaus, wo sie die Leitung der Färberei in der Textilwerkstatt übernommen hatte.

Auch nach ihrem Studium gibt es Konstellationen, wie Bergner mit Neuraths Bildpädagogik in Berührung gekommen sein kann. Im Frühjahr 1931 schloss sie sich in Moskau der „Roten Bauhaus-Brigade“ an und begann in der damals größten Möbelstofffabrik der Sowjetunion eine Arbeit als Textilgestalterin. Auch Neurath ging 1931 nach Moskau. Er beteiligte sich dort am Aufbau eines neuen Instituts für Bildstatistik (Isostat), das auf Initiative der „Österreichischen Gesellschaft zur Förderung der geistigen und wirtschaftlichen Beziehungen mit der UdSSR“ gegründet wurde.7 Unterstützt von einem Expertenteam aus Wien verpflichtete er sich, bis 1934 zwei Monate pro Jahr sowjetische Zeichner und Linolschneider auszubilden. Nicht zuletzt da Bergner Teil des westeuropäischen Exilnetzwerks war, ist es naheliegend, dass sie über Neuraths bildpädagogische Methodenarbeit in der Sowjetunion in Kenntnis war, wenn der direkte Kontakt zwischen beiden auch unwahrscheinlich und nicht belegt ist.

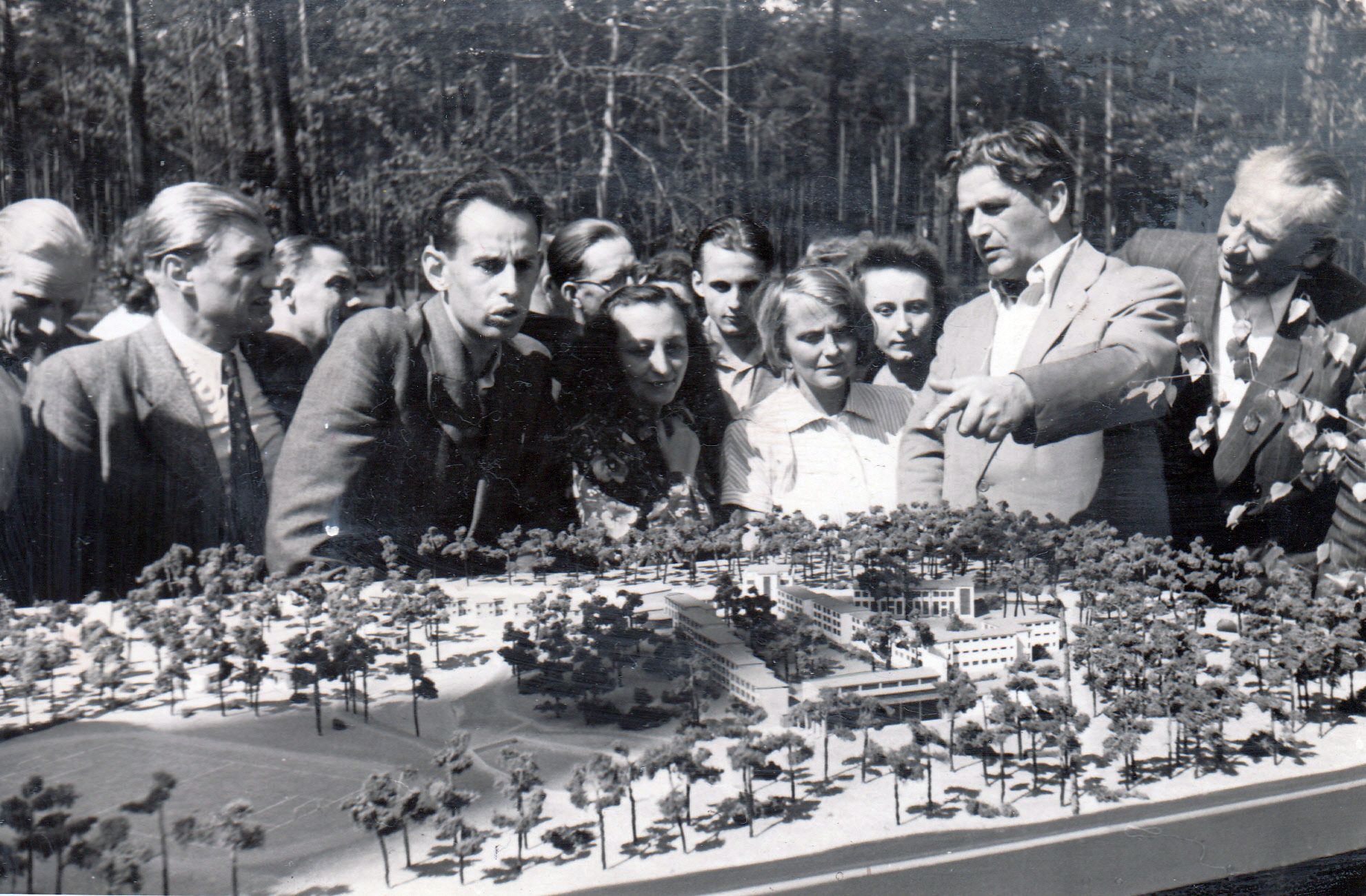

und László Moholy-Nagy CIAM IV.jpg?w=964)

.jpg?w=245&h=163&c=1)

.jpg?w=245&h=163&c=1)