Learning From

Paul Klee, Carpet, 1927, Hans-Willem Snoeck, Brooklyn, New York, Photo © Edward Watkins.

Book cover of Ernst Fuhrmann: Tlinkit und Haida, Folkwang Verlag GmbH, Hagen 1922.

Raoul D’Harcourt: Textiles of Ancient Peru and their Techniques, University of Washington Press, Seattle 1962.

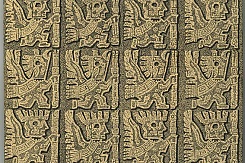

Arthur Baessler collection, Shirt, Tiahuanaco (=Tiwanaku), 0–700 (?), Peru

© Ethnologisches Museum der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz, photo: Claudia Obrocki.

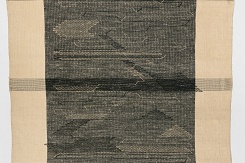

Anni Alber, Black–White–Gray, 1927, © The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2019.

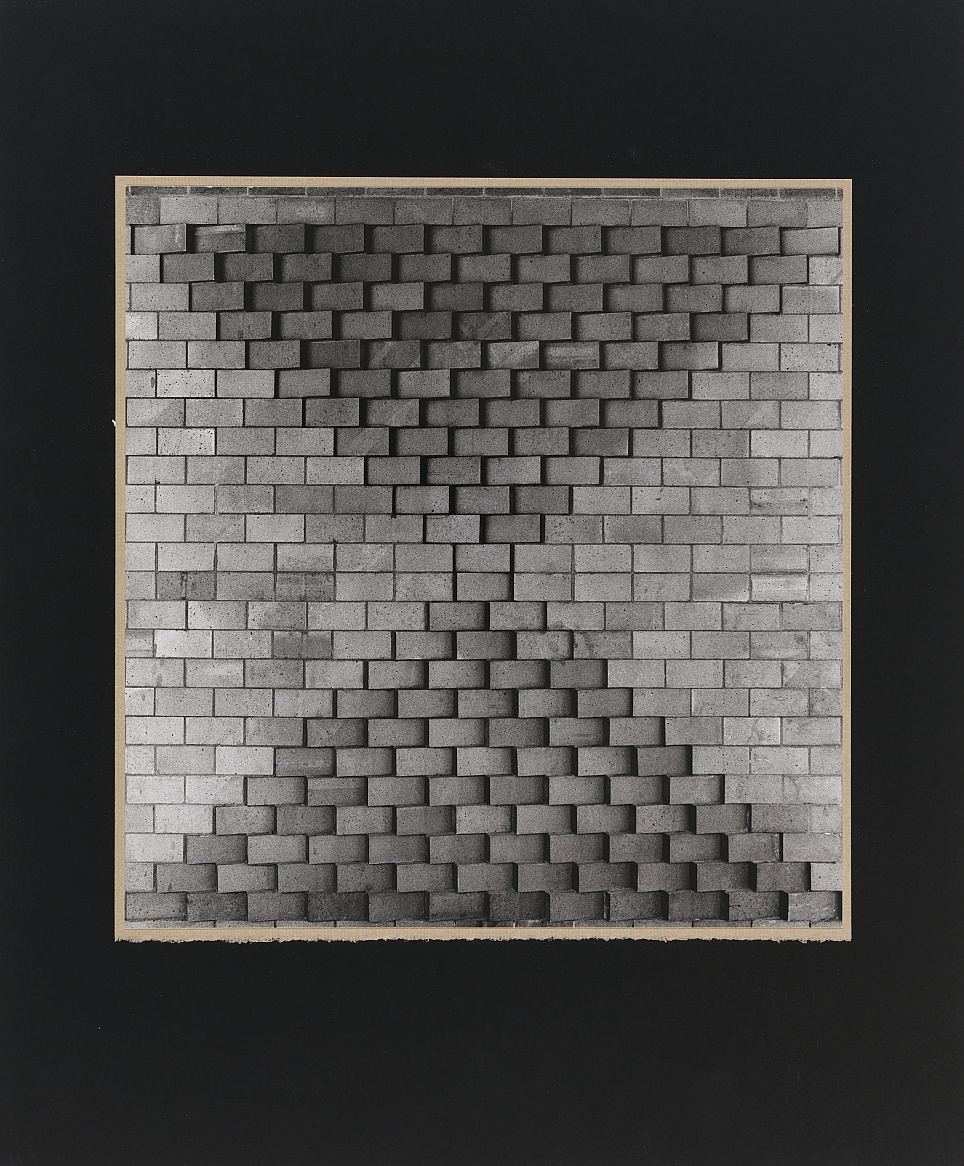

Josef Albers, Loggia Wall at RIT, 1967

The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, © The Josef and Anni Albers Foundatio / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2019.

.jpg?w=964)

Rose Slivka, "New Tapestry", in: Craft Horizons, March/April 1963

Lena Bergner, Draft of a hand loom, ca. 1936–39, Bauhaus Dessau Foundation

© American Craft Council / Heirs to Lena Bergner.

Eduard Gaffron Collection, Khipu, Inca 1450–1550, Huacho, Peru

© Photo: Ethnologisches Museum der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz, photo: Claudia Obrocki.

Anne Wilson, "Net Fence" detail, 1975, Cotton and jute cord, raffia, bamboo supports, 96 x 45 x 20 inches overall.

Courtesy of the artist.

Lenore Tawney, Mask, ca. 1967, Linen, pre-Columbian beads, shell, horsehair

Photos: George Erml; Courtesy: Lenore G. Tawney Foundation.

.jpg?w=964)

Marguerite Wildenhain, Double Face pot, 1960–70, Luther College, Decorah, photo: Grant Watson, © Luther College.

Kader Attia, Signs of Reappropriation as Repair, 2017, Single projection of 80 slides, Courtesy of the artist.

from: Maghreb Art Magazine, No. 3, 1965, © Mohamed Melehi.

Poster exhibition of Farid Belkahia, Mohamed Chabâa, Mohamed Melehi, Théâtre National

Mohamed V, design: Mohamed Melehi, 1965, Toni Maraini Collection, © Mohamed Melehi.

Painted ceiling of Mohamed Melehi, Hotel Les Roses du Dades, Kelaa M'Gouna, 1968–69

Architects: cabinet Faraoui et de Mazières, archives: Faraoui et de Mazières.

Door from the Musée Tiskiwin, Collection of Bert Flint, photo: Maud Houssais.

Departing from Paul Klee’s drawing, Teppich (Carpet) of 1927, the exhibition chapter Learning From addresses the study and appropriation of cultural production from outside the modernist mainstream by focusing on non-Western sources, but also European folk traditions, the work of outsider artists and children. An engagement with premodern artefacts and practices was a constant feature of the work of teachers and students at the Bauhaus. This abiding interest continued to inform the approach of many “Bauhaus-people” following the school’s closure in 1933.

In the United States of the mid-twentieth century, exploring the local craft practices and pre-Columbian cultures of North, Central and South America helped to develop both the formal language of abstraction and new styles of weaving and fiber art based on precolonial forms and techniques. By questioning the division between the high and low arts, the Bauhaus paved the way for a broader contestation of the classical orientation of European art academies. However, while often used to deconstruct this binary, the study of non-Western art and cultural practice failed to take into account the sometimes violent and frequently illegitimate appropriation of cultural goods during and after the colonial period, as well as the social, economic and political disruption European colonialism left in its wake throughout the Americas, Africa and Asia.

Thus, while incorporating popular, indigenous and Afro- Brazilian cultures into the lexicon of Brazilian modernism acted as an effective counter model to European modernist influence, this development occurred while colonial violence perpetrated against Brazil’s indigenous population continued unabated. In postrevolutionary Mexico and postcolonial Morocco, the program of translating precolonial cultural production into the language of modernity acquired a sociopolitical dimension, as illustrated by the aesthetic strategies of El Taller de Gráfica Popular (The Workshop for Popular Graphic Art, or TGP) in Mexico and the École Supérieure des Beaux Arts in Casablanca both demonstrate. Learning From demonstrates that Bauhaus modernism was indebted to transcultural encounters, albeit within a network of asymmetrical power relations, while also revealing how, in the context of decolonization and struggles for cultural self-determination, the synthesis of premodern and modern art the Bauhaus instigated generated a set of aesthetic, cultural and economic practices that challenged and contested paternalistic Eurocentric cultural paradigms.

Learning From was realized together with the SESC Pompeia (São Paulo) and the Haus der Kulturen der Welt (Berlin), in cooperation with Elissa Auther, Erin Alexa Freedman (New York City), Anja Guttenberger (Berlin), Maud Houssais (Rabat) and Luiza Proença (São Paulo). French-Algerian artist Kader Attia and Brazilian architect and theorist Paulo Tavares each developed new works for this chapter.

from: Shuttle-Craft Bulletin, March 1941.

from: Black Mountain College Bulletin, No. 5, 1938.

Publié dans: Maghreb Art, 1966.

Courtesy of Mohammed Melehi and Toni Maraini.

Publié dans: Integral, No. 12–13, 1978.

Courtesy of Toni Maraini.

Publié dans: Souffles, No. 7–8, 1967.

Courtesy of Abdellatif Laâbi.

Part I. from: Shuttle-Craft Bulletin, 1957.

Part II from: Shuttle-Craft Bulletin, 1957.

from: Black Mountain College Bulletin, Vol. 6, No. 4, May 1948. Reproduced with permission of North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources.

Oral history interview, 2004 February 3 and March 11.

from: Denise Y. Arnold & Elvira Espejo: The Andean Science of Weaving, Thames & Hudson Ltd. London 2015, pp. 18–44.

in: HARTS & Minds: The Journal of Humanities and Arts, Vol. 2, No. 3, Issue 7, 2016.

- EN

- DE

- FR

_crop.jpg?w=245&h=163&c=1)

Kopie.jpg?w=245&h=163&c=1)