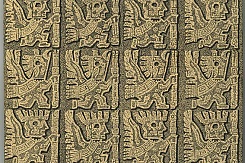

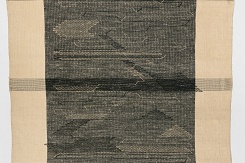

In the final chapter of her book On Weaving Anni Albers wrote: “The efforts of weavers in the direction of pictorial work have only in isolated instances reached the point necessary to hold our interest in the persuasive manner of art. Experimental—that is, searching for new ways of conveying meaning—these attempts to conquer new territory (my italics) even trespass at times into that of sculpture.”1 Elaborating on this, she refers to a photograph of Dark River, a free-hanging work woven from open-ended cross-pieces and differently grouped warp threads by Lenore Tawney (1907–2007), an American practitioner of fiber art. In her book, Albers makes mention of a select group of contemporary weavers, Tawney among them. From the perspective of Albers’ Bauhaus philosophy, it appears Tawney’s weaving techniques, inspired by Amerindian cultures (such as the use of open warp), struck a special note. Interested herself in Pre-Columbian weaving, she seems to have realized just how innovative Tawney’s work was.

In my essay I will explore this “new territory” Albers mentions which Tawney supposedly was conquering, addressing the closely connected question of whether this term might, in fact, be ill-suited. While it is legitimate to describe weaving in the form of fiber art2 and its expansion into the male-dominated domain of sculpture as an act of “conquering”—and it is likely that this is primarily what Albers meant—the search for new ways of conveying meaning that Albers addresses in On Weaving is tied closely to colonial semantics. And while in her book the power imbalance between practitioners is, to my mind, adequately addressed (though Albers invokes these semantics in a rather naïve way), I believe that in Tawney’s case it falls wide of the mark. Or am I wrong? My aim is to examine the ways in which Tawney appropriated non-European vernacular objects and craft techniques as well as Amerindian and East Asian ontologies, and to focus on at the role which the Bauhaus played in these appropriation strategies.

_crop.jpg?w=245&h=163&c=1)

Kopie.jpg?w=245&h=163&c=1)